You won’t want to miss this one hour zoom presentation with Sandy Skoglund.

Sandy and Holden talk about the ideas behind her amazing images and her process for making her photographs.

Sandy is part of our current exhibition, “Rooms that Resonate with Possibilities”.

Luntz: We are delighted to have Sandy Skoglund here today with us for a zoom call. She is part of our exhibition, which centers around six different photographers who shoot interiors, but who shoot them with entirely different reasons and different strategies for how they work. Sandy, I’ve sort of been a fan of yours and have been showing your work for 25 years. You have this wonderful reputation. And truly, I consider you one of the most important post-modern photographers. But to say that you’re a photographer is to sell you short, because obviously you are a sculptor, you’re a conceptual artist, you’re a painter, you have, you’re self-taught in photography but you are a totally immersive artist and when you shoot a room, the room doesn’t exist. Everything in that room is put in by you, the whole environment is yours.

So what Jaye has done today is she’s put together an image stack, and what I want to do is go through the image stack sort of quickly from the 70s onward. And we’ll talk about the work, the themes that run consistent through the work, and then, behind me you can see a wall that you have done for us, a series of, part of the issue with Sandy’s work is that there, because it is so consumptive in time and energy and planning, there is not, like other photographers, several hundred pictures to choose from or 100 pictures to choose from.

There’s major work, and in the last 40 years most of the major pictures have all found homes. The additions were never big editions. So what Sandy has done for us, which is amazing since the start of COVID is to look back, to review the pictures that she made, and to allow a small number of outtakes to be made as fine art prints that revisit critical pictures and pictures that were very, very important in the world and very, very important in Sandy’s development so that’s what you’re looking at behind me on the wall, and we’re basically the only ones that have them so there is something for collectors and they’re all on our website. So people have responded to them very, very well. A lot of them have been sold. But it’s something new this year that hasn’t been available before. So it’s a way that you can participate if you really want to own Sandy’s work and it’s very hard to find early examples. So let’s take a look at the slide stack and we won’t be able to talk about every picture, because we’re going to run out of time. But what I would like to do is start so I can get Sandy to talk about the work and her thoughts behind the work.

1970s

Luntz: So we start in the 70s with, you can sort of say what was on your mind when this kind of early work was created, Sandy.

Skoglund: Probably the most important thing was not knowing what I was doing. Really not knowing what I was doing. But the one thing I did know was that I wanted to create a visually active image where the eye would be carried throughout the image, similar to Jackson Pollock expressionism. Where every piece of the rectangle is equally important. And I wanted to bury the person within this sort of perceived chaos. And so that was where this was coming from in my mind. I was also shopping at the 5 and 10 cent store up on 34th Street in Manhattan. And, as a child of the 50s, 40s and 50s, the 5 and 10 cent store was a cultural landmark for me for at least the first 10, 10-20 years of my life.

Skoglund: So the plastic spoons here, for example, that was the first thing that I would do is just sort of interplay between intentionality and chance. Meaning the chance was, well here are all these plastic spoons at the store. I’ll just buy a bunch of them and see what I can do with them when I get them back to the studio.

Luntz: What I want people to know about your work is about your training and background. You’re a prime example of everything that you’ve done leading up to this comes into play with your work. You were in a period of going to art school, trained as a painter, you had interest in literature, you worked in jobs where you decorated cakes, worked in fast food restaurants. So, so much of what you do comes out later in your work, which is interesting.

1980s – Radioactive Cats

Luntz: Radioactive Cats, for me is where your mature career began and where you first started to sculpt. Can you talk about this piece briefly?

Skoglund: Well, coming out of the hangers and the spoons and the paper plates, I wanted to do a picture with cats in it. And I knew that, from a technical point of view, just technical, a cat is almost impossible to control. And in 1980, wanting these small F-stop, wanting great depth of field, wanting a picture that was sharp throughout, that meant I had to have long exposures, and a cat would be moving, would be blurry, would maybe not even be there, so blurry. So it just kind of occurred to me to sculpt a cat, just out of the blue, because that way the cat would be frozen. I had a few interesting personal decisions to make, because once I realized that a real cat would not work for the piece, then the next problem was, well, am I going to sculpt it or am I going to go find it?

And I think in all of Modern Art, Modern and Contemporary Art, we have a large, long, lengthy tradition of finding things. Like from Marcel Duchamp, finding things in the culture and bringing them into your artwork, dislocating them. And I felt as though if I went out and found a cat, bought one let’s say at Woolworths, a tchotchke type of cat. That it wouldn’t be coming from my soul and my heart. It would be, in a sense, taking the culture’s representation of a cat and I wanted this kind of deep, authenticity. This was the rupture that I had with conceptualism and minimalism, which which I was deeply schooled in in the 70s. So this idea of trying to find a way to include my spirit, my feeling, my limitations, too, because the cats aren’t perfect by any means.

But the other thing that happened as I was sculpting the one cat is that it didn’t look like a cat. So now I was on the journey of what makes something look like a cat? I mean, is it the tail? Is it the feet? Is it the gesture? So, that catapulted me into a process of repetition that I did not foresee. And that process of repetition, really was a process of trying to get better at the sculpture, better at the mimicist. I’d bring people into my studio and say, “What does this look like? What kind of an animal does it look like?” So I probably made about 30 or 40 plaster cats and I ended up throwing out quite a few, little by little, because I hated them. I mean they didn’t look, they just looked like a four legged creature. And I decided, as I was looking at this clustering of activity, that more cats looked better than one or two cats. So this sort of clustering and accumulation, which was present in a lot of minimalism and conceptualism, came in to me through this other completely different way of representative sculpture.

1980s – Revenge of the Goldfish

Luntz: So if we go to the next picture, for most collectors of photography and most people that understand Contemporary Photography, we understand that this was a major picture. You were with Leo Castelli Gallery at the time. The picture itself, as well as the installation, the three-dimensional installation of it, was shown at the Whitney in 1981, and it basically became the signature piece for the Biennial, and it really launched you into stardom. Andy Grunberg writes about it in his new book, “How Photography Became Contemporary Art,” which just came out. You were the shining star of the whole 1981 Whitney Biennial. And I think it had a major, major impact on other photographers who started to work with subjective reality, who started to build pictures. You weren’t the only one doing it, but by far you were one of the most significant ones and one of the most creative ones doing this. Can you talk a little bit about the piece and a little bit also about the title, “Revenge of the Goldfish?”

Skoglund: Well, I think long and hard about titles, because they torture me because they are yet another means for me to communicate to the viewer, without me being there. You know, to kind of bring up something that maybe the viewer might not have thought about, in terms of the picture, that I’m presenting to them, so to speak.

So, “Revenge of the Goldfish” comes from one of my sociological studies and questions which is, we’re such a materialistically successful society, relatively speaking, we’re very safe, we aren’t hunter gatherers, so why do we have horror films? This huge area of our culture, of popular culture, dedicated to the person feeling afraid, basically, as they’re consuming the work. So this led me to look at those titles. Revenge then, for me, became my ability to use a popular culture word in my sort of fine art pictures. So “Revenge of the Goldfish” is a kind of contradiction in the sense that a goldfish is, generally speaking, very tiny and harmless and powerless. But in a lot of my work that symbology does have to do with the powerless overcoming the powerful and that’s a case here. Where the accumulation, the masses of the small goldfish are starting to kind of take revenge on the human-beings in the picture.

Luntz: And to me it’s a sense of understanding nature and understanding the environment and understanding early on that we’re sort of shepherds to that environment and if you mess with the environment, it has consequences. You said that, when we spoke before, about 25 years ago, you said the goldfish was really the first genetically engineered living creature.

Skoglund: I’m not sure it was the first. I know that Chinese bred them. That’s all I know, thousands of years ago.

Luntz: So for me I wanted also to tell people that you know, when you start looking and you see a room as a set, you see monochromatic color, you see this immense number of an object that multiplies itself again and again and again and again. By 1981, these were signature elements in your work, which absolutely continue until the present. So by 1981, I think an awful lot of the ideas that you had, concepts about how to make pictures and how to construct and how to create some sense of meaning were already in the work, and they play out in these sort of fascinating new ways, as you make new pictures.

1980s – A Breeze at Work

Luntz: So, “A Breeze at Work,” to me is really a picture I didn’t pay much attention to in the beginning. But then I felt like you had this issue of wanting to show weather, wanting to show wind. So what happened here? And for people that don’t know, it could have been very simple, you could have cut out these leaves with paper, but it’s another learning and you’re consistently and always learning. You’re making them out of bronze. So can you tell me something about its evolution?

Skoglund: Well, I think you’ve hit on a point which is kind of a characteristic of mine which is, who in the world would do this? I mean there are easier, faster ways. So the answer to that really has to be that the journey is what matters, not the end result. So much of photography is the result, right? It’s the picture. It’s not really the process of getting there. So, this sort of display of this process in, as you say, a meticulously, kind of grinding way–almost anti-art, if you will.

I know when I went to grad school, the very first day at the University of Iowa, the big chief important professor comes in, looks at my work and says, “You have to loosen up.” And so I really decided that he was wrong and that I was just going to be tighter, as tight as I could possibly be. And I think, for me, that is one of the main issues for me in terms of creating my own individual value system within this sort of overarching Art World.

But you do bring up the idea of the breeze. Here again the title, “A Breeze at Work” has a lot of resonance, I think, and I was trying to create, through the way in which these leaves are sculpted and hung, that there’s chaos there. And in our new picture from the outtakes, the title itself, “Chasing Chaos” actually points the viewer more towards the meaning of the work actually, in which human beings, kind of resolutely are creating order through filing cabinets and communication and mathematical constructs and scientific enterprise, all of this rational stuff. And in the end, we’re really just fighting chaos.

1980s – Fox Games

Luntz: I think it’s important to bring up to people that a consistent thread in a lot of your pictures is about disorientation and is about that entropy of things spinning out of control, but yet you’re very deliberate, very organized and very tightly controlled. So out of that comes this kind of free ranging work that talks about a center that doesn’t hold. That talks about disorientation and I think from this disorientation, you have to find some way to make meaning of the picture.

Again, you’re sculpting an animal, this is a more aggressive animal, a fox, but I wanted people to understand that your buildouts, your sets, are three-dimensional. So, photographers generally understand space in two dimensions. You, as an artist, have to do both things. You have to understand how to build a set in three dimensions, how to see objects in sculpture, in three dimensions, and then how to unify them into the two-dimensional surface of a photograph. That’s a complicated thing to do. How do you go about doing that?

Skoglund: Eliminating things while I’m focusing on important aspects. So, in the case of Fox Games, the most important thing actually was the fox. That’s what came first. You could ask that question in all of the pieces. What was the central kernel and then what built out from there? The restaurant concept came much, much later. But first I’m just saying to myself, “I feel like sculpting a fox.” That’s it. There’s no rhyme or reason to it. I just thought, foxes are beautiful. I like how, as animals, they tend to have feminine characteristics, fluffy tails, tiny feet. I liked that kind of cultural fascination with the animal, and the struggle to sculpt these foxes was absolutely enormous.

Luntz: What are they made of?

Skoglund: They were originally made of clay in that room right there. That is the living room in an apartment that I owned at the time. And I sculpted the foxes in there and then I packed everything up and then did this whole construct in the same space.

Luntz: You said it basically took you 10 days to make each fox, when they worked. So I mean, to give the person an idea of a photographer going out into the world to shoot something, or having to wait for dusk or having to wait for dark, or scout out a location. Think how easy that is compared to, to just make the objects it’s 10 days a fox. And the question I wanted to ask as we look at the pictures is, was there an end in sight when you started or is there an evolution where the pictures sort of take and make their own life as they evolve?

Skoglund: Your second phrase for sure. There’s no preconception. The preconception or the ability to visualize where I’m going is very vague because if I didn’t have that vagueness it wouldn’t be any fun. It would really be just like illustrating a drawing. So if you want to keep the risk and thrill of the artistic process going, you have to create chances. You have to create the ability to change your mind quickly. Keep it open, even though it feels very closed as you finish. But yes you’re right.

This idea that the image makes itself is yet another kind of process. It’s an art historical concept that was very common during Minimalism and Conceptualism in the 70s. I don’t know if you recall that movement but there was a movement where many artists, Dorthea Rockburne was one, would just create an action and rather than trying to be creative and do something interesting visually with it, they would just carry out what their sort of rules of engagement were. So that concept where the thing makes itself is sort of part of what happens with me.

Luntz: With Fox Games, which was done and installed in the Pompidou in Paris, I mean you’ve shown all over the world and if people look at your biography of who collects your work, it’s page after page after page. Your career has been that significant. But this is the first time, I think, you show in Europe correct?

Skoglund: Correct.

Luntz: An installation with the photograph. So you reverse the colors in the room. Why? Was it just a sort of an experiment that you thought that it would be better in the one location?

Skoglund: No, no, that idea was present in the beginning for me. So I knew I was going to do foxes and I worked six months, more or less, sculpting the foxes. Not thinking of anything else. I’m always interested and I can’t sort of beat the conceptual artists out of me completely. So the conceptual artist comes up and says, “Well, if the colors were reversed would the piece mean differently?” Which is very similar to what we’re doing with the outtakes. If the models were doing something different and the camera rectangle is different, does, do the outtake images mean something slightly different from the original image?

So I knew that I wanted to reverse the colors and I, at the time, had a number of assistants just working on this project. So I took the picture and the very next day we started repainting everything and I even, during the process, had seamstresses make the red tablecloths.

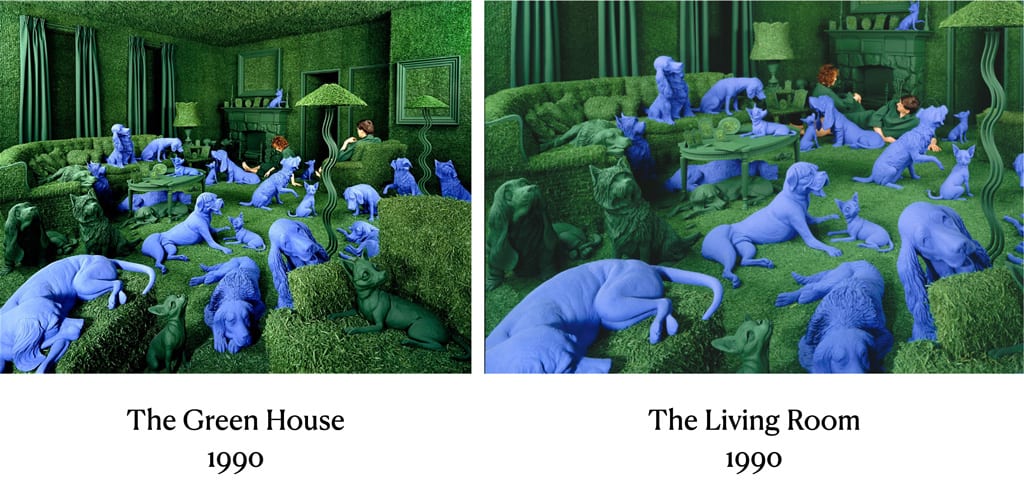

1990s – The Green House

Luntz: I want to let people know when you talk about the outtakes, the last slides in the presentation show the originals and the outtakes.

So moving into the 90s, we get “The Green House.” There’s a series of pictures that deal with dogs and with cats and this one is a really soothing, but very strange kind of interaction of people and animals. Can you give me some sense of what the idea behind making the picture was?

Skoglund: I have to say I struggle with that myself. I know that when I started the piece, I wanted to sculpt dogs. I mean that was interesting to me. I’ve never been fond of dogs where I’m really fond of cats. But I love them and they’re wonderful and the more I looked into it, doing research, because I always do research before I start a project, there’s always some kind of quasi-scientific research going on. I realized that the dog, from a scientific point of view, is highly manipulated by human culture. The same way that the goldfish exists because of human beings wanting small, bright orange, decorative animals. This, too is a symbol or a representation of they are nature, but nature sculpted according to the desires of human beings.

So that kind of nature culture thing, I’ve always thought that is very interesting. That we are part of nature, and yet we are not part of nature. So, the way I look at the people in “The Green House” is that they are there as animals, I mean we’re all animals. And so, who’s to say, in terms of consciousness, who is really looking at whom? Right? I mean do the dog see this room the same way that we see it? And that’s why I use grass everywhere thinking that, “Well, the dogs probably see places where they can urinate more than we would see the living room in that way.” So, those kinds of signals I guess.

Luntz: Very cool. And you mentioned in your writing that you want to get people thinking about the pictures. What they see and what they think is important, but what they feel is equally important to you. So you see this cool green expanse of this room and the grass and it makes you feel a kind of specific way. And if you’re a dog lover you relate to it as this kind of paradise of dogs, friendly dogs, that surround you. When you sculpted them, just as when you sculpted foxes and the goldfish, every one has a sort of unique personality. You didn’t make a mold and you did not say, “I’ve got 15 dogs and they’re all going to be the same. I’m just going to put some forward and some backwards.” Every one is different, every one is a variation. So, it’s a pretty cool. I like the piece very much.

1990s – Gathering Paradise

Luntz: This one is a little more menacing “Gathering Paradise.” So, is it meant to be menacing?

Skoglund: Yeah, it is. Sometimes my work has been likened or compared to Edward Hopper, the painter, whose images of American iconographical of situations have a dark undertone. And I am a big fan of Edward Hopper’s work, especially as a young artist. So, the title, “Gathering Paradise” is meant to apply to the squirrels. And the squirrels are preparing for winter by running around and collecting nuts and burying them. I think, even more than the dogs, this is also a question of who’s looking at whom in terms of inside and outside, and wild versus culture.

I think I’m always commenting on human behavior, in this particular case, there is this sort of a cultural notion of the vacation, for example. I find interesting that you need to or want to escape from what you are actually living to something else that’s not that. And I saw the patio as a kind of symbol of a vacation that you would build onto your home, so to speak, in order to just specifically engage with these sort of non-activities that are not normal life.

1990s – The Cocktail Party

Luntz: Okay “The Cocktail Party” is 1992. It’s a piece that we’ve had in the gallery and sold several times over. It’s interesting because it’s an example of how something that’s just an every day, banal object can be used almost infinitely–the total environment of the floors, the walls, and how the cheese doodles not only sort of define the people, but also sort of define the premise of the cocktail party. Is it a comment about society, or is it just that you have this interest in foods and surfaces and sculpture and it’s a way of working?

Skoglund: Well, this period came starting in the 90s and I actually did a lot of work with food. This is the only piece that actually lasted with using actual food, the cheese doodles. And it’s in the collection of the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas. So the installation itself, it still exists and is on view right now.

Skoglund: But here you see the sort of quasi-industrial process. Now to me, this just makes my day to see this picture. It’s just organized insanity and very similar to growing up in the United States, organized insanity. Working at Disneyland at the Space Bar in Tomorrow Land, right? Working in a bakery factory while I was at Smith College. My parents lived in Detroit, Michigan and I read in the newspaper “Oh, we’re paying, I’m pretty sure it was $12.95, $12.95 an hour,” which at the time was huge, to work on the bakery assembly line at Sanders bakery in Detroit. So there I am, studying Art History like an elite at this college and then on the assembly line with birthday cakes coming down writing “Happy Birthday.”

The sort of disconnects and strangeness of American culture always comes through in my work and in this case, that’s what this is, an echo of that. But I didn’t do these cheese doodles on their drying racks in order to create content the way we’re talking about it now. I really did it for a practical reason, which was that the cheese doodles, in order to not fall apart, had to be covered with epoxy.

1990s – Atomic Love

Luntz: So this begins with the cheese doodles and you’ve got raisins, you’ve got bacon, you’ve got food, and people become defined by that food, which is an interesting. Is it a comment about post-war? About America being a prosperous society and about being a consumptive based society where people are basically consumers of all of these sort of popular foods?

Skoglund: I don’t see it that way, although there’s a large mass of critical discourse on that subject. To me, that’s really very simplistic. And no, I really don’t see it that way. I’ve always seen the food that I use as a way to communicate directly with the viewer through the stomach and not through the brain. If the viewer can recognize what they’re looking at without me telling them what it is, that’s really important to me that they can recognize that those are raisins, they can recognize that those are cheese doodles. And I think it’s, for me, just a way for the viewer to enter into. It’s something they’ve experienced and it’s a way for them to enter into the word. “Oh yeah, I’ve seen that stuff before. I know what that is.” But it’s used inappropriately, it’s used in not only inappropriately it’s also used very excessively in the imagery as well.

Luntz: There is a really good book that you had sent us that was published in Europe and there was an essay by a man by the name of Germano Golan. And it was really quite interesting and they brought up the structuralist writer, Jacques Derrida, and he had this observation that things themselves don’t have a meaning–the raisins, the cheese doodles. What gives something a meaning is the interest of what the viewer takes to it and the things that are next to it. Meanings come from the interaction of the different objects there and what our perception is. So, are you cool with the idea or not? After working so hard and after having such intention in the work, of saying that the work exists and has meanings on so many different levels to different people and sometimes they don’t correspond at all, like what I was saying, to what you thought and you’re saying, well, that’s a very simplistic reading that it’s popular culture, it’s a time of excess, that the Americans have plenty to eat and they have this comfort and that sort of defines them by the things that are available to them. So…

Skoglund: Yeah I love this question and comment, because my struggle in life is as a person and as an artist. The ideas and attitudes that I express in the work, that’s my life. That’s my life. So I don’t feel that this display in my work of abundance is necessarily a display of consumption and excess. I feel as though it is a display of abundance. That we’re surrounded by, you know, inexorably, right? I mean, you go drive across the United States and you see these shopping centers. They’re all very similar so there comes all that repetition again. And they’re full of stuff. What is the strategy in the way in which shops, for example, show things that are for sale? They don’t put up one box, they put up 50 boxes, which is way more than one person could ever need. But they want to show the abundance. They want to display that they have it so that everybody can be comfortable and we’re not going to be running out.

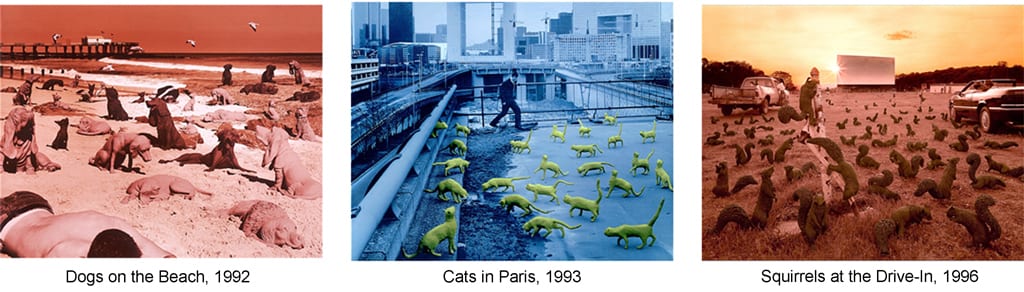

Luntz: These are interesting because they’re taken out of the studio, correct?

Skoglund: Right.

Luntz: But had you used the dogs and cats that you had made before? Was it reappropriating these animals or did you start again?

Skoglund: These are the same, I still owned the installations at the time that I was doing it. So yeah, these are the same dogs and the same cats.

Luntz: And this time they get outside to go to Paris. They go to the drive-in.

Skoglund: They escaped. They get outside.

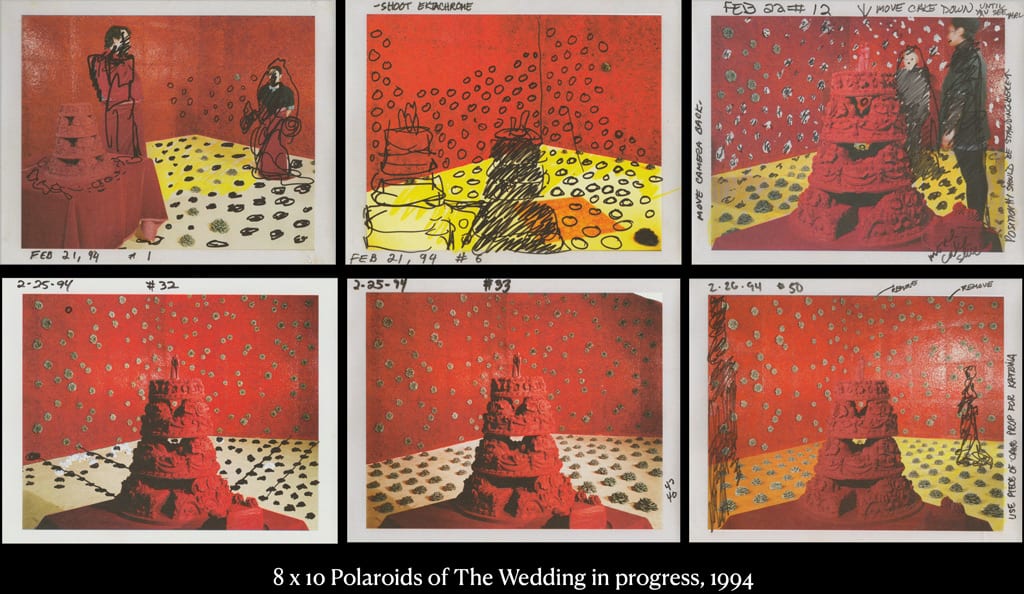

1990s – The Wedding

Luntz: This one has this kind of unified color. This sort of overabundance of images. It’s kind of a very beautiful picture. And this is how it’s sort of made, right? Some of the development of it?

Skoglund: Right those are 8 x 10 negative, 8 x 10 Polaroids.

Luntz: Do they start with drawings?

Skoglund: No, I draw all the time, but they’re not drawings, they’re little sketchy things. These are done in a frantic way, these 8 x 10 Polaroids, which I’m not using anymore. You know Polaroid is gone, it’s a whole new world today. But, at the time of the shooting, the process of leading up to the shoot was that the camera is there and I would put Polaroid back on the camera and I would essentially develop the picture. At that point, I’ve already made all the roses. I knew the basic ingredients and elements, but how to put them together in the picture, would be done through these Polaroids. I would take the Polaroids home at the end of the day and then draw on them, like what to do next for the next day.

Luntz: Okay, so the floor is what marmalade, right?

Skoglund: Marmalade and strawberry jam.

Luntz: And the flowers are made of?

Skoglund: They’re all different and handmade in stoneware. They’re ceramic with a glaze.

Luntz: So it’s an amazing diversity of ingredients that go into making the installation and the photo. So it’s marmalade and it’s stoneware and it’s an amazing wide variety of using things that nobody else was using. And it’s a learning for you. I think you must be terribly excited by the learning process.

Skoglund: Oh yeah, that’s what makes it fun.

1990s – Walking on Eggshells

Luntz: This picture and this installation I know well because when we met, about 25 years ago, the Norton had given you an exhibition. And when the Norton gave you an exhibition, they brought in “Walking on Eggshells.” When I originally saw the piece, there were two people that came through it, I think they were dressed at the Norton, but they walked through and they actually broke the eggshells. This is interesting because, for me, it, it deals in things that people are afraid of.

Skoglund: Right.

Luntz: And the amazing thing, too, is you could have bought a toilet. You could have bought a bathtub. You could have bought a sink. But you didn’t. You learned to fashion them out of a paper product, correct?

Skoglund: Right. I certainly worked with a paper specialist to do it, as well, but he and I did it.

Luntz: And you’ve got the rabbit and the snake which are very symbolic in what they mean.

Skoglund: True, in Western culture.

Luntz: And the tiles and this is a crazy environment.

Skoglund: Well, I kind of decided to become an art historian for a month and I went to the library because my idea had to do with preconceptions. I’ve already mentioned attributes of the fox, why would there be these feminine attributes? You know of a fluffy tail. And you’re absolutely right. The the snake is an animal that is almost universally repulsive or not a positive thing. However, when you go back and gobroadly to world culture, it’s also seen, historically, as a symbol of power. So power and fear together.

So the wall tiles are all drawings that I did from books, starting with Egypt and coming into the present day–the American Easter Bunny. So, the rabbit for me became transformed. It was always seen, historically, as a representative of spring because it actually is, in Europe, the first animal that seems to appear when the when the snows melt. And so this transmutation of these animals, the rabbit and the snake, through history interested me very much and that’s what’s on the wall.

Luntz: So, before we go on, in 1931 there was a man by the name of Julian Levy who opened the first major photography gallery in the United States. He showed photography, works on paper and surrealism. When he opened his gallery, the first show was basically called “Waking Dream.” And so my question is, do you ever consider the pieces in terms of dreams? Do you think in terms of the unreality and reality and the sort of interface between the two? Because a picture like this is almost fetishistic, it’s almost like a dream image to me. Is that an appropriate thought to have about your work or is it just moving in the wrong direction?

Skoglund: Well, I think that everyone sees some kind of dream analogy in the work, because I’m really trying to show. I mean, what is a dream? A dream is convincing. It’s not, it’s not just total fantasy. You’re usually in a place or a space, there are people, there’s stuff going on that’s familiar to you and that’s how it makes sense to you as a dream. So I don’t discount that interpretation at all.

I personally think that they are about reality, not really dream reality, but reality itself. Mainly in the sense that what reality actually is is chaos. It’s chaos. And it’s only because of the way our bodies are made and the way that we have controlled our environment that we’ve excluded or controlled the chaos. So that’s why I think the work is actually, in a meaningful way, about reality. It’s letting in the chaos.

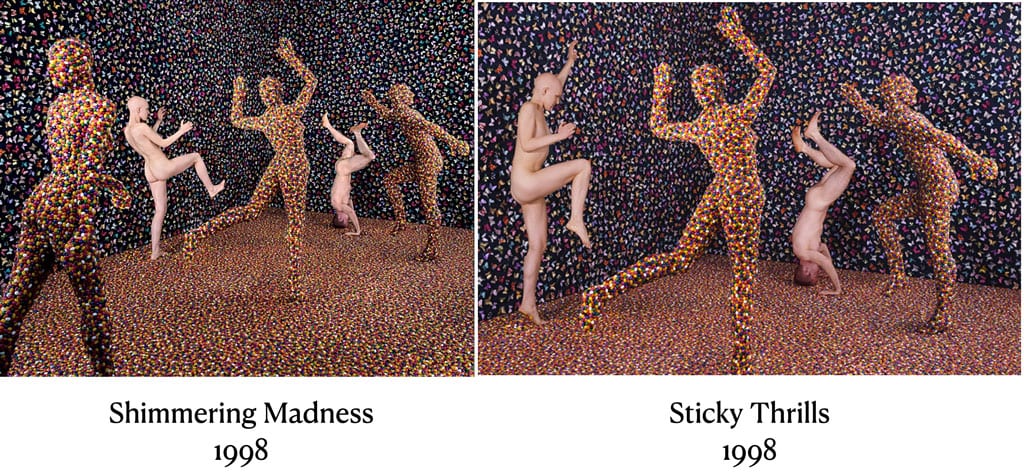

1990s – Shimmering Madness

Luntz: “Shimmering Madness” is a picture that we’ve had in the gallery and clients love it. But it’s a kind of fantasy picture, isn’t it? With the butterflies that, in the installation, The fabric butterflies actually moved on the board and these kind of images that are made of an armature with jelly beans, again popular objects. But the surfaces are so tactile and so engaging. Where did the inspiration for “Shimmering Madness” come from?

Skoglund: Good question. Now we’re getting into, there’s not a room there, you know. There’s no room, it’s space. It’s not an interior anymore or an exterior. So this, in terms of being able to talk about what it actually meant to me, I think is very difficult. I guess in a way I’m going outside. With this piece the butterflies are all flying around. At the same time it has some kind of incongruities. The heads of the people are turning backwards looking in the wrong direction. The one thing that I feel pretty clear about is what the people are doing and what they’re doing is really not appropriate. They’re balancing on these jelly beans, they’re jumping on the jelly beans. My favorite part of the outtake of this piece called “Sticky Thrills,” is that the woman on the left is actually standing up and on her feet you can see the jelly beans stuck to the bottom of her foot. But in a lot of ways a lot of the cultural things that we’ve been talking about kind of go away.

2000s – Breathing Glass

Luntz: “Breathing Glass” is a beautiful, beautiful piece. We’ve had it and, again you had to learn how to fashion glass, correct?

Skoglund: Yes.

Luntz: So it’s a it’s a whole other learning. The people have this mosaic of glass tiles and shards. The armature of the people connected to them. If your pictures begin about disorientation, it’s another real example of disorientation. You eventually don’t know top from bottom. It’s really a beautiful piece to look at because you’re not sure what to do with it. It’s an enigma. And did it develop that way or was it planned out that way from the beginning?

Skoglund: I think you’re totally right. It’s almost a recognition of enigma, if you will. It’s almost outer space. Like where are we, right? Outer space? I don’t know, it kind of has that feeling. The one thing about this piece that I always was clear about from day one, is that I was going to take the picture with the camera and then turn it upside down. So that to me was really satisfying with this piece. That final gesture.

2000s – Raining Popcorn

Luntz: This one, I love the piece. We have it in the gallery now. This was done the year of 9/11, but it was conceived prior to 9/11, correct?

Skoglund: Correct.

Luntz: So is there any sense it’s about a rescue or it’s about the relationship between people. It almost looks like a sort of a survival mode piece, but maybe that’s just my interpretation.

Skoglund: I don’t see how you could see it otherwise, really, Holden. I mean it’s rescuing.

Luntz: It fascinates me.

Skoglund: I think during this period I’m becoming more sympathetic to the people that are in the work and more interested in their interaction. In the early days, I had no interest in what they were doing with each other. If you look at “Radioactive Cats,” the woman is in the refrigerator and the man is sitting and that’s it. You know, they’re basically alone together. And that’s a sort of overarching theme really with all the work. We actually are, reality speaking, alone together, you know, however much of the together we want to make of it. But yes, in this particular piece the raison d’être, the reason of why they’re there, what are they doing, I think it does have to do with pushing back against nature. I mean they’re just, I usually cascade a whole number of, I would say pieces of access or pieces of content.

Even the whole idea of popcorn to me is interesting because popcorn as a sort of celebratory, positive icon goes back to the early American natives. We found popcorn poppers in the southwest. So I was just interested in using something that had that kind of symbology.

2000s – Picnic on Wine

Luntz: This was a commission, right? You don’t normally do commissions.

Skoglund: No, it wasn’t a commission. There was a museum called Copia, it no longer exists, but they did a show and as part of the show they asked me to create a new piece. So I said well, I really wanted to work with a liquid floor. But the difficulty of that was enormous. I mean you have to build a small swimming pool in your studio to keep it from leaking, so I changed the liquid floor to liquid in glasses. That’s how this all came about.

2000s – Fresh Hybrid

Luntz: I want you to talk a little about this because this to me is always sort of a puzzling piece because the objects of the trees morph into half trees, half people, half sort of gumbo kind of creatures. What’s going on here?

Skoglund: I think it’s an homage to a pipe cleaner to begin with. And it’s a deliberate attention to get back again to popular culture with these chicks, similar to “Walking on Eggshells” with the rabbits. These chicks fascinate me. I’m very interested in popular culture and how the intelligentsia deals with popular culture that, you know, there’s kind of a split. There’s fine art and then there’s popular culture, art, of whatever you want to call that. And it’s possible we may be in a period where that’s ending or coming together. But, nevertheless, this chick, we see it everywhere at the time of Easter. It’s just a very interesting thing that makes like no sense. I mean it’s a throwaway, it’s not important. It’s, it’s junk, if you will. And yet, if you put it together in a caring way and you can see them interacting, I just like that cartoon quality I guess.

Luntz: And it’s an example, going back from where you started in 1981, that every part of the photograph and every part of the constructed environment has something going on. There is something to discover everywhere. So the eye keeps working with it and the eye keeps being motivated by looking for more and looking for interesting uses of materials that are normally not used that way.

2000s – Winter

Luntz: So we’ve got one more picture and then we’re going to look at the outtakes. “Winter” is the most open-ended piece. I’m not sure what to do with it. I know what’s interesting is that you start, as far as learning goes, this is involving CAD-cam and three-dimensional. So that’s something that you had to teach yourself. The work continues to evolve. You continue to learn. You continue to totally invest your creative spirit into the work. Can you just tell us a couple things about it?

Skoglund: Well, the foundation of it was exactly what you said, which is sculpting in the computer. From my brain, through this machine to a physical object, to making something that never existed before. The thrill really of trying to do something original is that it’s never been done before. Nobody ever saw anything quite like that. So that was the journey, the learning journey that you’re talking about and the sculptures are sculpted in the computer using ZBrush program. And it just was a never ending journey of learning so much about what we’re going through today with digital reality. I was happy with how it turned out.

I knew that I wanted to emboss these flake shapes onto the sculptures. So the first thing I worked with in this particular piece is what makes a snowflake look like a flake versus a star or something else. So it was really hard for me to come up with a new looking, something that seemed like a snowflake but yet wasn’t a snowflake you’ve seen hanging a million times at Christmas time. I also switched materials. My first thought was to make the snowflakes out of clay and I actually did do that for a couple of years. But they just became unwieldy and didn’t feel like snowflakes.

The other thing that I personally really liked about “Winter” is that, while it took me quite a long time to do, I felt like I had to do even more than just the flakes and the sculptures and the people and I just love the crumpled background. It’s actually on photo foil. Black photo foil which photographers use all the time. It’s a specific material that actually the consumer wouldn’t know about. It’s used in photography to control light. You cut out shapes and you tape them around the studio to move light around to change how lights acting and this crumpling just became something that I just was sort of like an aha moment of, “Oh my gosh, this is really like so quick.” After taking all that time doing the sculptures and then doing all of this crumpling at the end. For me, that contrast in time process was very interesting.

Luntz: But again it’s about it’s about weather. Just as, you know Breeze is about weather, in a sense it’s about the seasons and about weather. And that is the environment.

Revisiting Negatives

Luntz: I want to look at revisiting negatives and if you can make some comments about looking back at your work, years later and during COVID. You said you had time to, everybody had time during COVID, to take a step back and to get off the treadmill for a little bit. So when we look at the outtakes, how do your ideas of what interests you in the constructions change as you look back. From “The Green House” to “The Living Room” is what kind of change?

Skoglund: The people are interacting with each other slightly and they’re not in the original image. So there’s a little bit more interaction. That’s my brother and his wife, by the way.

Luntz: Wow, I was gonna ask you how you find the people for.

Skoglund: Yeah they are really dog people so they were perfect for this.

Luntz: Okay so this one, “Revenge of the Goldfish” and “Early Morning. In “Early Morning,” you see where the set ended, which is to me it’s always sort of nice for a magician to reveal a little of their magical tricks.

Skoglund: Well, during the shoot in 1981, I was pretending to be a photographer. So there are mistakes that I made that probably wouldn’t have been made if I had been trained in photography. One of them was to really button down the camera position on these large format cameras. An 8 x 10 camera is very physically large and heavy and when you open the back and put the film in and take it out you risk moving the camera. You know, it’s jarring it a little bit and, if it’s not really buttoned down, the camera will drift. So I loved the fact that, in going back through the negatives, I saw this one where the camera had clearly moved a little bit to the left, even though the installation had not moved.

Luntz: “The Wild Inside” and “Fox Games.” It’s quite a bit of difference in the pictures.

Skoglund: Right, the people that are in “The Wild Inside,” the waiter is my father-in-law, who’s now passed away. And actually, the woman sitting down is also passed away. And I don’t know where the man across from her is right now. But the two of them lived across the hallway from me on Elizabeth Street in New York. So these three people were just a total joy to work. I just loved my father-in-law and he was such a natural, totally unselfconscious model. I was endlessly amazed at how natural he was. Look at how he’s holding that plate of bread. I mean, just wonderful to work with and I don’t think he had a clue what what I was doing. It’s not as if he was an artist himself or anything like that. But it was really a very meaningful confluence of people.

And the most important thing for me is not that they’re interacting in a slightly different way, but I like the fact that the woman sitting down is actually looking very much towards the camera which I never would have allowed back in 1989. My original premise was that, psychologically in a picture if there’s a human being, the viewer is going to go right to that human being and start experiencing that picture through that human being. And so the kind of self-consciousness that exists here with her looking at the camera, I would have said, “No that’s too much contact with the viewer.” It makes them actually more important than in the early picture.

Skoglund: In the early pictures, what I want people to look at is the set, is the sculptures. All of the work that’s going on is the chaos and then the people inside are just there, the same way we are in our lives. Look at the chaos going on around us, yet we’re behaving quite under control. I mean, generally speaking, most of us. So this kind of coping with the chaos of reality is more important in the old work. This kind of disappearing into it. And in the newer work it’s more like I’m really in here now. What am I supposed to do? I think that there’s more psychological reality because the people are more important.

These people are a family, the Calory family. And she, the woman sitting down, was a student of mine at Rutgers University at the time, in 1980.

Luntz: So this is very early looking back at you know one of the earliest.

Skoglund: Yeah. The guy on the left is Victor. I was living in a tenement in New York, at the time, and I think he had a job to sweep the sidewalks and the woman was my landlady on Elizabeth Street at the time. I remember seeing this negative when I was selecting the one that was eventually used and I remember her arm feeling like it was too much, too important in the picture. But now I think it sort of makes the human element more important, more interesting. Introduces more human presence within the sculptures.

Skoglund: I can’t help myself but think about COVID and our social distancing and all that we’ve been through in terms of space between people. I don’t think this is particularly an answer to anything, but I think it’s interesting that some of the people are close and some are not that close. The two main figures are probably six feet away. So whatever the viewer brings to it, I mean that is what they bring to it. I think it’s just great if people just think it’s fun. What’s wrong with fun?

Luntz: There’s nothing wrong with fun. The other thing I want to tell people is the pictures are 16 x 20. So when you encounter them, you encounter them very differently than say a 40 x 50 inch picture. They’re very tight and they’re very coherent. I think that what you’ve always wanted to do in the work is that you want every photograph of every installation to be a complete statement. So the outtakes are really complete statements. They’re very tight pictures.

Luntz: This is the “Warm Frost.” They’re not being carried, but the relationship between the three figures has changed.

Skoglund: Yes, now the one who is carrying her is actually further away from the other two and the other two are looking at the fire. And then you have this animal lurking in the background as, as in both cases. So, I think it’s whatever you want to think about it. I did not know these people, by the way, but they were friends of a friend of mine and so that’s why they are in there.

Luntz: And the last image is an outtake of “Shimmering Madness.”

Skoglund: Which I love. I love the fact that the jelly beans are stuck on the bottom of her foot. And I remember after the shoot, going through to pick the ones that I liked the best. And thinking, “Oh she’s destroying the set. No, that can’t be.” But what could be better than destroying the set really? That’s also what’s happening in “Walking on Eggshells” is they’re walking and crushing the order thats set up by all those eggshells.

Luntz: And that’s a very joyful picture so I think it’s a good picture to end on. It’s a lovely picture and I don’t think we overthink that one.

Sandy, I haven’t had the pleasure of sitting down and talking to you for an hour in probably 20 years. I hate to say it. To me, you have always been a remarkable inspiration about what photography can be and what art can be and the sense of the materials and the aspirations of an artist. So thank you so much for spending the time with us and sharing with us and for me it’s been a real pleasure.

Skoglund: Thank you very much, Holden.