Stephen Wilkes visits the gallery for a special presentation during his exhibition, “Beyond the Horizon.” Throughout the presentation, Wilkes shares his journey capturing stunning photographs from around the world, including iconic locations like the Great Migration in Serengeti, the Northern Gannets in Scotland, and the Sand Hill crane migration in Nebraska. He discusses his techniques, challenges, and the deeper stories behind each photograph, highlighting the intricate connection between nature and humanity. From witnessing the melting ice in Greenland to the regenerative agriculture movement in Yellowstone, Wilkes emphasizes the urgency of preserving these environments.

Additionally, he introduces his latest project, “Tapestries,” which captures fleeting moments in vibrant, impressionistic compositions. Throughout his presentation, Wilkes expresses his passion for storytelling through photography and his commitment to raising awareness about environmental issues.

Luntz: First, I want to thank everybody on our team because each of us, all eight members, were involved in various ways in bringing the show to fruition. The pictures are complicated to print, frame, ship, and install. Additionally, there is web content to manage and production tasks related to the exhibition.

Everyone in the gallery shares great joy and respect for Stephen, and we all wanted to be part of this exhibition. I thank all of you for attending and allowing us to pursue our vision. When people inquire about the type of photographer we seek to represent in our shows, this is what we aim for.

There are dozens of people submitting JPEGs, sending unsolicited books, asking us for exhibitions. But there’s something special that happens in the world with so many photographic images – some become memorable while others don’t. We seek photographers who offer something truly original, who take the medium and make it their own, presenting work that captivates and draws you in, compelling you to return for another look.

These are the kind of pictures that Stephen creates – unique, complex, larger than life, and deeply authentic. He has found a way to make photography his own, understanding that a photograph is only as significant as its content. Stephen presents fascinating material in a manner that breaks new ground, expanding our understanding of what a photograph can be. While we showcase Stephen’s work, it’s worth noting that his influence extends globally, with monographs and museum shows highlighting his talent.

We are privileged and delighted to have both Stephen and Betty here today. Without Betty, Stephen’s work wouldn’t be possible; her role is critical, and we thank her for her contributions.

Two quick reminders: please silence your phones if you haven’t already, and save your questions for the end to ensure Stephen can share his insights uninterrupted. Thank you all for joining us – it promises to be a wonderful hour. And now, here’s Stephen.

Wilkes: Thank you so much, thank you all for being here today. I just want to say to Jodi, Holden, and the entire team here, it’s such an honor and a joy to work with this team. They’ve done such a remarkable job on this exhibition; it’s everything I’d hoped for and more, so thank you guys from the bottom of my heart, and thank you all for coming today. I’m going to share some of the backstory and really discuss how this work originated, where I’m going with it, and how it’s evolved over the last few years.

As Holden said, I’ve actually been doing this for 13 years. Believe it or not, ‘Day To Night’ was published in 2009, so it’s been quite a journey. My work was really inspired by a painting of ‘The Harvesters’ that I saw when I was in seventh grade, and it changed my life. I never understood that you could create an epic landscape like that and have an incredible narrative story within the landscape. So, I became fascinated with art history at that point in my life.

When I did this work, somebody called me and asked, ‘Stephen, were you inspired by this painting?’ I looked at the painting; it was the first time I had seen it in decades, and I realized it was a poster that hung in my room. It’s from Magritte’s ‘Les Lumieres’ series, and it’s interesting how things embed upon you as a young person and affect you long-term.

I immediately started to think about other artists that had influenced me, like Canaletto, because of the way he depicted Italy. I’ve done a number of day or night shots in Italy, and I actually used Canaletto as a scout. I go through his paintings because Venice looks exactly the same as when Canaletto painted it.

Albert Bierstadt is another big hero of mine; I got very interested in the Hudson River School painters. What I discovered with the Hudson River School was that these artists were painting light moving; it was not just a scene, but the light, depth, and three-dimensional quality made it very unique. As I looked at that, I began to think about how photography, with new technology, could potentially move in that direction.

This is another great painter from the Hudson River School who was also very concerned with the environment. Each of these artists, like Albert Bierstadt, that I’ve referenced, were all concerned about what was happening in the world, so their paintings really reflect the changes they were seeing.

The work started with an idea, which was first birthed when Life Magazine commissioned me in 1996 to do a photograph of Baz Luhrmann’s film ‘Romeo and Juliet.’ They asked me to create a four-page panoramic shot, but unfortunately, the set was square. Inspired by David Hockney, you can actually see in this picture, that’s a reflection in a mirror, and I shot 250 single images. Then I created this mosaic, like David Hockney, as the actual representation for the magazine.

But when I put this work together in my studio, I realized the idea of having Clare Danes and Leonardo kissing in the reflection was something I’d never seen before – the idea that I was changing time in a photograph. And that’s where the genesis of the idea really happened.

People always ask me, ‘How do you do this thing?’ So, I wanted to give this great description, and it’s really this great combination of art and science together. What I do is decide where day begins and night ends, and I call that a time-vector. My time vectors can run sometimes left to right on what I call the x-axis. They can run vertically on the y-axis, or they can run diagonally on the z-axis.

So, what I do basically is I take the concept of time, which Einstein describes as this fabric that gets bent and distorted based on the gravitational field, and I take this idea of fabric and flatten it into a two-dimensional photograph. So, I build what I call a master plate of the scene.

This picture was taken while I was 60 feet in the air over Coney Island for 16 hours, photographing. It was in July. What I did was capture day on the right and night on the side of the Ferris Wheel. At this point in the series, I really knew that I wanted the Ferris Wheel at night and the day at the beach. Then, I built the master plate, and as time went on, I took very specific moments. I’m literally like a street photographer, capturing things that I see in front of my lens. There’s nothing automated about what I do. Everything I do follows the most traditional manner of photography, much like Ansel Adams or Carlton Watkins, all these early masters. I’m just using a digital back, and what I do in post-production is revolutionary in terms of what happens in the medium of photography.

So, the work started in New York City. It became a deep passion of mine; I love New York. I wanted to create images of New York that celebrated what I felt about the city. I shot from a high perspective, which enabled me to see into a scene and capture very specific moments as time changes.

Times Square

This is, of course, Times Square. It’s funny because my photographs, after 13 years, are historical now. This picture doesn’t exist anymore because there are no yellow cabs in New York. Uber has changed everything.

Brooklyn Bridge

And then there’s the Brooklyn Bridge. This picture took almost four years to make; it was an enormous effort. I must mention my wife Betty. I couldn’t do anything without her. She’s just the best, and she’s the one who produces these things. I get the easy job of just producing the pictures.

This is what my work looks like up close. It’s wonderful that you all are coming to see this exhibition, and I hope you get the opportunity to really take the time to look closely at our photographs. But for those of you at home who are live streaming, that’s what the work looks like up close. I’m telling stories in my photographs. To me, the narrative is almost as important as anything else that I do.

Capturing moments like Sunday in the Park was really special. I was under the Manhattan Bridge in a crane for 18 hours. And I say to people, I was essentially almost tone-deaf afterward because listening to the B and D Train run every three minutes, you can’t even imagine how loud it was.

Across America

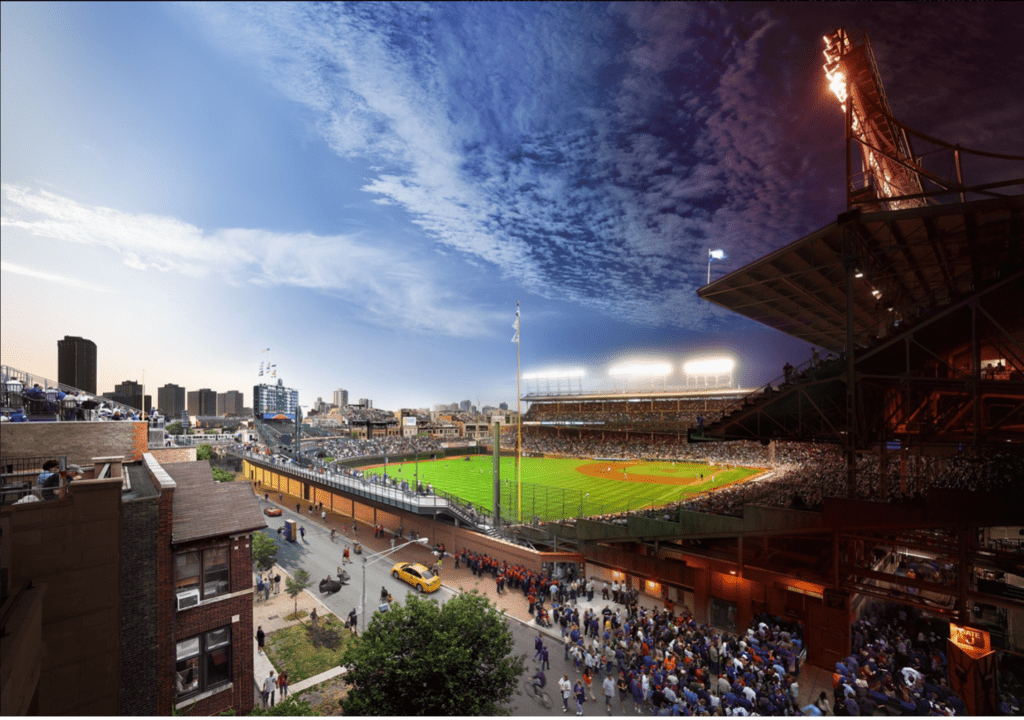

I started then moving the work across America. I went to Chicago, and again, I was fascinated by history. History has been a big theme in my work for many years. Many of you know my work on Ellis Island that I documented—the abandoned rooms of Ellis Island many years ago. So, I’m drawn to history, and of course, I heard about the great Wrigley Field, and they were going to build a scoreboard to block the view of the left field. I had decided I had to capture Wrigley Field before they built that scoreboard. And so, this photograph is, in fact, historical. It’s a Day to Night twilight doubleheader, which is also kind of a rare event these days, but it was quite special to capture that.

I then shot the great American Cup Race. I was actually photographing from Alcatraz, and I’m the only photographer who’s ever been allowed to be on top of a lighthouse, literally for 24 hours, to make this picture. And this was the final race, which is again a historical moment in the history of America’s Cup.

Miami, I mean, here we are. This is also a bit of history because this is at the peak of Covid, with a full moon in October. And when you look closely at this picture, you really get to see people in their Halloween costumes. It’s not just Covid masks; they’re wearing costumes, so it was an amazing experience. The ocean was closed for that picture.

Europe

I obviously then started to migrate the work to Europe, and I was then in Paris. Of course, the great Notre Dame. Making this photograph was very special. Never in my wildest dreams would I think that it would be damaged the way it has been. My dream and hope is that it returns to its grandeur and beauty that you see in this photograph.

These are the tulips. People look at this picture and go, ‘well how complicated is that?’ It’s actually more complicated than some of my animal photographs because once a tulip opens, they cut the bulbs. They literally cut the tops off, the heads of the flowers. So, they’re not interested in selling the flower; they’re interested in bulbs. And when the bulbs are at their peak, in terms of nutrients, it’s when the flower is fully open. So, what I had to do is work with this farmer and try to gauge when the flower was going to open because I didn’t want to get there and have all the tulips be gone. And so we ended up spending weeks. I actually made more than one trip to make this photograph, but it was worth it. And you see in the photograph of this picture, that’s not a window but actually World War II bunkers. I tell the story of how the Nazis tried to invade Bergen; that’s where I made this picture. That is where they tried to come in from; that’s where I shot this picture. It has a really important significance.

Stonehenge, oh the times I got to photograph Stonehenge by some incredibly strange luck, which I don’t really question, I just embrace it. They have a pagan wedding the day I’m doing this picture, and so you actually see these people dressed full-on. It looked like something out of that famous TV series with the vampires in the 1970s. That’s what they were dressed like; it was fantastic, but it really made my photograph.

I then moved over to Venice, and I heard about this thing called the historical regatta, which had been going on literally since the 1500s. Same boats, the costumes, and I thought, wouldn’t that be cool. I’m going to do it Day to Night, play with time, but I’m going to go backwards in time, and so that’s why I made this picture. And then again, I was obsessed with Italy and the history of Italy, and I was always fascinated.

This is the race in Siena, The Palio, and probably one of the more challenging storytelling images I’ve ever had to do. This is 18 hours of photographing. To let you know, I spent 18 hours and basically 90 seconds is the race. So I get all these great moments, and then if the race does not start or if I miss the moment, my camera jams. Within that 90 seconds, I have no photograph. So much of what I require needs all kinds of alignment in terms of luck and everything. So it was a fantastic experience though.

If you look closely in this picture, you can see the beginning of the race. They actually take the horses out for a walk-through, and then as time changes, you see there’s actually a prayer service at the church, and then you see the parade start. On the right-hand side, you see the horses; they look like they’re pulling up. That’s the false start. The group behind is the actual start, and then to the right is the winning contrade. And then to the right of them, you see all of the contrade going completely berserk. So, it really tells the story of the entire day.

Ipanema Beach, I was on a lifeguard stand for God knows, it was 20 hours doing this picture. It was fantastic fun.

Jerusalem, and then my work really made a pivot. So, I was starting to think. I was in National Geographic. I had done my first story for them, and I started doing the Day to Night work, and I wanted to show them and bring them into what I was doing. I felt there was an opportunity to storytelling with this work in a unique way. And so I pitched them on the idea of doing the national parks for the 100th anniversary and paying respect and homage to some of the great photographers that went way before me. People like Eadweard Muybridge and Carleton Watkins who used technology in a way that changed the way we think about our national parks.

The National Parks

So, I pitched them on Yosemite Day to Night, and at the time, they were hesitant. I said, “Okay, I’m just going to go out and do this one on my own,” and I made this photograph. I remember sending it to the photo editor at Geographic, and at the time when she said, “Sarah Leene,” she wrote me back in about five minutes, “Okay, how do we get involved in this? We want to get you a grant to do this series.” And this was shot from the great viewpoint of Tunnel View. I was actually on top of the tunnel in Tunnel View for 36 hours, okay, anchored with rope to make this photograph, but it was worth it.

The Grand Canyon, shot from the top of the Desert Tower. Again, 36 hours of photographing. People often ask me, “How do you even pay attention for that long?” What I do is almost like a deep meditation. In a world where we are constantly connected by devices and being constantly bombarded, responding to text messages, I go out there and I literally just look at a place for 24 to 36 hours. It’s this deeply enriching experience, and I think you’ll see in some of the new work I really feel that part of my work, the depth, what you feel when you look at my pictures, is that I’m putting that kind of time in, and you get to see things you never would see if you just walk into a scene and look around and walk away. I get to see all kinds of things happening. And so that series launched me into another image.

Wildlife

I wanted to photograph the Great Migration for the first time, so I had this idea: I’m going to go to the Serengeti during the peak of the migration. I got there, but there was a severe drought going on, and so the animals were not migrating. So what I ended up doing was I discovered this watering hole, and I watched it for several days, almost five or six days. I just kept going back and seeing all the animals coming in and out. And I had built a crocodile blind on my truck.

What I witnessed was nothing short of biblical. I captured, as time changed, all of these competitive species sharing a watering hole—water, this resource that we’re all supposed to have wars going for in the next few decades because there’s such a shortage of water globally. But the animals seem to understand something we don’t. They seem to understand almost like a different kind of consciousness. They seem to thrive on the idea that, you know what, you might be a threat to me, I might be a threat to you, but when it comes to drinking and bathing, we’re all even, right? And that’s what they did. And I watched it for 26 hours, and it changed my life. It really was a pivotal moment for me to use this technique to tell stories like this, because I felt like I witnessed something that needed to be shared.

So, this is, again, as you look, we’re fortunate to have this print here in the gallery, and when you get close and look at it, you will see the stories that I recorded. People often ask me, “Oh, there weren’t that many animals there, right?” I said, “I’ll tell you how many animals there were. I have single photographs, single pictures, where you can’t see the water in the scene. That’s how many animals we have.” So, the elephants, if you look at the picture on the right-hand side, day is beginning. You can actually see the color of the light in the upper, middle portion of the photograph. You see the migration of the wildebeests actually starting early in the morning. As your eye moves diagonally across this photograph, like this, time is changing. So, time changes this way, that center moment that you’re seeing was extraordinary.

When I shoot these pictures, I shoot such high-resolution photographs that my computer actually begins to run out of memory, so I have to wipe my computer and back up everything. That usually happens twice during a big shoot. And in the early days, I couldn’t actually shoot on cards, so I had to actually stop shooting for five minutes to back up. And the fear for me is always, I’m going to miss something. What could happen in that five minutes? Maybe there’s a lion that comes out, or something happens. And what ended up happening here was my assistant, thank God, got me active again in 4 minutes and about 30 seconds, exactly at that moment. I had a 20x 24 window that was my window into the blind, so I couldn’t see anything except through this 20x 24 window that’s what I was shooting at of, and I leaned my head out after we were reconnected and there was no animals and all of a sudden on the right-hand corner of my eye I see this huge group of elephants marching in like the Jungle Book it was unbelievable and so I watched them and I just literally shooting, shooting, shooting. But if my assistant had been 30 seconds later, I would never have had that picture.

So, this is in a place called Robson Bight. It’s one of the most extraordinary places I’ve ever been in my life. It’s the only place in the world where orca whales come, families of them, for a spa treatment. The Bite has rocks in it that don’t exist anywhere else, and the orcas come and they rub against these rocks.

I had given a TED Talk in 2016 at the dream conference, and a gentleman approached me. He said, ‘You would love where I work.’ I go, ‘Where do you work?’ He says, ‘I work in this place called Robson Bight.’ I go, ‘Wow.’ He goes, ‘Now, it’s the most amazing place because we have cruise ships, we have bald eagles, we have every imaginable kind of species. And then we’ve got these whales, these Orca families that come in and rub on the rocks.’ And I said, ‘I don’t know how could I make this picture?’ And this is what ended up happening. You’re going to see, you’re hearing these are the whales, you’re going to hear underwater as they approach. Not that little dog, he wants to be an orca, but he’s not.

But you know what was magical about this? The scientists gave me their underwater microphones. And so I had a walkie-talkie so I could listen to the whales coming in. And one of the highlight moments for me was early in the morning. I hear a sound, but it’s not like that orca. And I got behind my camera right away because it must have been a big, I knew it was a big whale, turns out it was a humpback whale. And that’s the one you can see it up in here, he’s blowing all that steam, that, that was the humpback whale.

And, at this point, Canada became a real passion project for me. I created this photograph in an amazing place called Bella Coola. Up north of Vancouver, there’s a river and a lodge there. With the permission of this fabulous lodge and National Park, they allowed me to build a scaffolding. I spent 36 hours photographing these bears. It was quite amazing because, for the first time, I was studying wildlife in a habitat. I brought this photograph to the National Geographic Society, and they were very generous in supporting me with a grant to create these pictures to tell the story of what’s happening with endangered species and habitats in Canada. That’s the project I continue to work on now.

Bird Migrations

In between that photograph, I got another story with a dear editor of mine, Kathy Moran, who was really my main editor at National Geographic for many years. She said, ‘Well, Stephen, do you think you could do this picture with birds?’ And I’m like, ‘Day to Night with birds, birds move, I mean, well, maybe we can do it with nesting birds during migration.’

So I went to a place called Lake Bogoria to photograph the Lesser Flamingo. That’s my blind; this is one of the most magnificent places I’ve ever been. And, when you get above these birds, it’s absolutely spellbinding.

But I wanted to share this with you because I want to share the scale of what it is that I see when I go to these places. Part of what I’m so drawn about is I’ve spent so many years shooting things that are great tragedies, and trying to make them look beautiful. My focus now is to shoot things that are so beautiful to make you feel that you don’t want to lose them. I’m trying to overwhelm you with a sense of awe and wonder.

That’s what I feel when I go to these places, and this picture you’re seeing 36 hours of photographing from a blind. These are the Lesser Flamingos. Time changes vertically, so Day to Night, and the moment you’re looking at now? That’s a single moment. And that single moment happened because there’s a species of birds, they’re called marabou storks, and those Marabou stalks love to feed on Lesser Flamingos and they work and they hunt together like a pack of Velociraptors, and they’re very, very militaristic and they’re very strategic, and they attacked all of these birds on the bottom of the photograph, and that one moment, literally, every bird that was on the ground went up in the air. So it was absolutely spectacular. And people often ask me, how do you decide which, where’s day start, where does night begin, all that kind of stuff. How could I not have that moment in the photograph?

So then, I had to travel to Scotland, Edinburgh, and there was a species there called the Northern Gannets, and I like birds, but these are not the nicest birds in the world, let me just start there. So I ended up traveling to, it’s literally a lighthouse on this island, it’s called Bass Rock, I got special permission to get on it, it was 200 steps of slime, I can’t even begin to describe, and I was with these birds personally in their nests for 36 hours, this was my entertainment, they are so aggressive with each other, and they were aggressive with me, they like to stab you in the calf muscle when you get close, but the 36 hours was worth it, this was the photograph I made.

And again, to do what I do, I have to be intimate with the subject, and that is really challenging when you’re dealing with wildlife, but this is again, I have a moon full moon rising, a lot of times when I do nature I try to go out during full moons because, there’s no nightlight so I need the moonlight to really light the night side. People often ask me, oh well I’d love to go to Bass Rock, I said I highly recommend it, I just wouldn’t stay there for 36 hours, but it is a spectacular place.

Then I traveled to one of the remote Southern islands in the Falklands, called Steeple Jason. I had to scout the island; it was an 8-mile island. There’s probably only about 50 people who’ve ever set foot on this island, it’s that remote. It’s owned by WCS (Wildlife Conservation Society), and they have one house on the island and one 1972 Land Rover. My assistant and I laid in a Tussock and photographed, and most of the time people look at my work and they go, ‘Well, I mean, you know that rain did that really happen there?’

I get to tell the narrative story of a species, again, Art and Science. I study them like a scientist does, uh, but over the course of 36 hours, I see a mother teaching a baby how to fly. I see the communication between a male and a female. These animals breed for life, 50 years pf life. Mothers will fly 5,000 miles just to feed their young. And when the young become teenagers, they fly back and they come back and they have these things called gaggles and they reminisce about what it was like, what they’re doing, and they’re like, ‘Where are you fishing these days?’ ‘I don’t know, what about you?’ And it’s like teenagers. I mean, it’s fantastic.

And then I traveled to Nebraska along the Platte River. If you’d ever told me that Nebraska would be one of the most beautiful things I’d ever seen in my life, I’d go, ‘Seriously? Nebraska?’ But it’s kind of flat, isn’t it? But I’ll tell you what, if you get a chance, put it on your bucket list. The Sandhill crane migration is one of the most spectacular things you’ll ever see in your lifetime.

This is like seeing hundreds of thousands of birds. These birds, by the way, have 8ft wingspans just to give you an idea. I spent 36 hours in a blind I built almost 2 months before the actual migration, and once I’m in it, I’m in it. I was stuck there, and let me tell you, at night, it got colder than you don’t want to know.

But here are the birds. You can see them sleeping in the morning. Now they go out in the morning light to roost, and they’re flying to get food. They’re so loved in Nebraska that most of the farmers till their fields for these birds, so they have lots of food to eat. At night, they come back and again they roost along the river.

Colder Climates

And then I traveled to Canada again, continuing my Day to Night Canadian project, and I photographed the polar bears. We have a print of that here as well, and this was a really remarkable experience for me because I was so lucky to see the bears.

With polar ice melting, these bears in Hudson Bay will not be able to go for food unless the ice gets cold enough and firm enough for them to travel across. The issue, as photographers, is that if you are there when the ice gets cold enough, you might be lucky to catch them. If you miss it by an hour, the bears are gone, and you’ll never see them. So there’s so much luck involved in whether or not it happens.

But what I loved about this photograph was you can actually see the melting ice in the morning. The bottom of the photograph is morning, and time changes vertically along the y-axis here. And that was a full moon, and those are the actual rays of the moonlight in the sky, something I’ve never seen before.

And then I traveled to Greenland, intending to capture a photograph of rising seas and melting ice. However, what I discovered was part of the beauty of what I’m able to do when I study a place and photograph it. I was there during July in 2019, during what was called the Great Melt.

During this time, 198 billion tons of ice liquefied into the Atlantic Ocean. What struck me was that as the ice melted, I saw more humpback whales than I had ever seen in my life. They were gorging themselves, taking advantage of the abundance of food created by the melting ice.

I observed that when the ice melts, sediment is released into the water, activating the growth of plankton. This abundance of plankton attracts krill, and in turn, the krill attract the whales. It’s a top-down feeding situation, where each level of the ecosystem benefits from the one below it.

This experience made me realize the vital role that sea ice and glacial ice play in feeding the ocean’s wildlife. Without them, the entire ecosystem, from fish to whales, would struggle to thrive. It was a picture and a story that I wasn’t expecting to tell, but it became an important narrative of this photograph.

I traveled to Iceland, where my work began to focus on environmental realities. One of the places I visited was the Blue Lagoon, a remarkable site where geothermal energy is harnessed. The lagoon itself is created from wastewater recycled from the geothermal production of electricity, making it one of the world’s most renowned spas.

During my time there, I had the incredible fortune of capturing both a snowfall and the northern lights in a single photograph, all in one day. It was a stroke of luck that allowed me to encapsulate these natural phenomena in one stunning image.

I went to Iceland, and again, my work started to think about things that were environmentally really happening. I love the idea, this is the Blue Lagoon, being able to capture this regenerative, this amazing, this is geothermal energy and basically the lagoon is the wastewater being reused from the geothermal production of electricity and become one of the hottest spas in the world. And I was able to very luckily capture a snowfall and the northern lights in one photograph, in one day.

I pitched National Geographic on a project involving a nearby volcano, the Shield Volcano. The process involved creating a Day-to-Night photograph of the volcano. I utilized a 3D model for scouting purposes and traveled to the site via helicopter, as depicted in the accompanying video.

For me, I would like to get elevated because when I change time it’s really important that I have a certain type of perspective but also it’s exciting, to get a certain perspective. We watch the light change, we watch things that happen, there’s nothing automated about it, my eyes kind of scan. So, we’re all set up here, really. Inc., we have looking at the volcano. The winds are quite stiff, it’s going to be a cold night. It’s been a challenge. Certainly, theses volcanos are not, they’re unlike anything I’ve ever shot, in terms of predictability. I think that if my work is so much about, embracing sort of uncertainty, here, this is certainly one of those situations where we’re embracing it all, and hopefully walk away with something very special.

And we did walk away with something very special. There is a big print of it here, so I hope you guys take a look at it, but it was truly one of the highlights of my life, making this picture. I can’t begin to tell you what a show it was. I actually stood for 20 hours. I never sat down for 20 hours. And, to a point where I can’t wear gloves, and the temperature was quite cold, and my knuckles were just swelling, and I looked like a prize fighter. But it was all worth it because this thing turns out, the day that I made this picture was probably the most active single day of a volcano through the entire time period it was erupting. So, it was very special on a lot of levels, and I wanted to make a picture that showed the molten lava, which without lava, there is no life, and I wanted the sun setting behind that lava because without the sun, we have no life, and I really wanted to make that connection for people and make that part of the essence of this photograph.

America the Beautiful

Then, National Geographic commissioned me to do a story on America the Beautiful for the 30 for 30 initiative. So, they asked me to create four Day-to-Night photographs that actually captured some of the most important places that need to be saved by 2030.

So, the first place they sent me to was this place called Bears Ears National Park. This is what some of my working conditions are like when you look at this photograph. This is a 60-mph wind for about 12 hours. We had sandbags literally holding down all my gear, and as that… that wasn’t enough, we had my assistant and myself holding down the cameras. I don’t think you can describe it as anything but sand plastic, so when you look at this scenery. This was the cover, and this was the September issue of the Geographic.

We hiked in, it was about an hour hike with 80lbs of equipment on our backs, and I certainly think that while some of the hike was pretty moderate, the end part of the hike was quite challenging. But what I captured was unlike anything ever seen. It is such a unique place, a place that was threatened by a previous administration. They wanted to essentially build a mine in this place, and now it is protected, and thankfully it is. You see hikers come in there at various times of the day. You have to be quite serious to even find this place, but the magic in this photograph is I caught a full moonrise that happened to be on a day that was Passover, it was a day that was Easter, and it was a day that was Ramadan. And if that wasn’t enough for me, it turns out that there’s a four planetary alignment that happens once every 33 years on the day that I’m photographing, and that’s what the story is.

This area is controlled by the Navajo Nation. This is actually called The Citadel, and the Citadel is the outpost where Navajos defended their land, so it is really historically a very, very important part of their culture, their history, but also the planets and the stars are so critical to so much of what they would draw, the pictographs, the things that they would draw, the things that they would study, so the fact that I was able to get the Rising Sun on the left here and the moon rising and the planets and that’s the moonlight all in one picture to tell that story was really special.

Then, I traveled to the Oregon coast for this place called Shi Shi Beach, and here you can see me. I am actually sitting on a rock that’s about, it doesn’t look it but that rock is almost 30 ft high, and I’m photographing for 20 hours as the tide changes. To get to that location took me 4 hours of hiking, 2 hours through a rainforest in almost shin-deep mud with 70 to 75lb backpacks on. And then when I got to the end of that mud trail, I had to hike 155 steps down to get to the beach. Once we got to the beach, I have another hour and a half hike to get to this place called The Arches. It’s run by the Macau Nation, it’s co-managed by the United States Park Service, but this is really their land, and this is their, um, their, their spiritual spot. It’s called The Arches, and these rock formations, they call sea stacks, and it’s unlike any place I’ve ever been in my life. So what you’re seeing here is time changes, high tide is on the left side of the picture, and you actually see the tide change across as you move from left to right.

We wanted to capture something about agriculture, and farming in particular, and cattle grazing. There’s a movement now called Regenerative Agriculture, especially with cattle, and there’s a ranch out there called the JL Bar Ranch in Yellowstone. I made this picture about two weeks prior to the great Yellowstone River flooding, and the bridge that I took to get to this location is gone now, so I was so fortunate to be able to make this photograph. The background you’re looking at, those are the Crazy Mountains, a very famous mountain range, and as time changes, you can actually see this herd of bulls ebbing and flowing as the day goes on. Once they graze an area, they move them to a different area.

And then, this is my most recent work that you have right here, Day to Night Chilko Lake, focusing again on the grizzly bears. This picture is really about how the bears and salmon are so interconnected, and how the loss of one element in an environment can ripple through everything else. I spent over 36 hours capturing and telling this story. Remarkably, I had no wind for almost 4 days, which allowed me to capture a mirrored lake, enhancing the narrative of the photograph.

Tapestries

And lastly, I’m going to share a new body of work I’ve been developing called Tapestries. If day and night for me is like a symphony, as my son, who’s a musician, describes it, then Tapestries is like jazz. It’s a fitting comparison because, like jazz, Tapestries is about improvisation and capturing the essence of a moment.

Tapestries involves taking pictures over the course of generally 4 to 8 seconds, all done in camera with multiple exposures. There’s no post-work or retouching involved, no layering or complexities like Day-to-Night. It’s about capturing fractional time, condensing a fleeting feeling or emotion into just a few seconds.

For me, Tapestries is about recreating the emotional resonance of a moment, the feeling I have when I’m in a particular place. It’s akin to how impressionist painters worked, their eyes moving around a scene, capturing the essence of what they saw and felt over the course of an afternoon of painting. It’s these elements that translate into the painting, making viewers feel what the painter felt. And that’s what I aim to achieve with Tapestries—invoking the emotions and sensations of a moment through photography.

Lake Como, we have a print of this one here, so you should check it out. They just evoke, uh, there’s a great joy when I make these pictures, um, there’s a letting go that I experience. Part of my work really is about this idea that I like being uncomfortable when I work. I always say that if I’m comfortable, then I’m really not working hard enough. And when I do tapestries, uh, I feel like I’m just jumping off something. I’m just letting go. I don’t know where it’s going to go. I don’t know what’s going to really happen, but it’s a translation, I think, in terms of what’s in my mind’s eye at a given moment and the feeling that I have there.