Discover Marcus Leatherdale’s captivating journey from his early days in New York City’s art scene, where he worked alongside Robert Mapplethorpe, to his profound exploration of Indian tribal life through photography. Delve into his unique perspectives on self-portraiture, hidden identities, and the timeless tradition of Indian tribes, beautifully captured with his Hasselblad camera and split-tone printing technique. Follow his ongoing mission to document and preserve the disappearing cultures of India while supporting charitable causes through his work. Explore the intersection of art, anthropology, and humanity in Leatherdale’s evocative imagery.

Luntz – What impact did your time as Robert Mapplethorpe’s office manager in the early 1980s have on your work? What did you learn from also being one of his subjects?

Leatherdale – Robert was very inspirational in my early years. Working as his studio manager in New York City gave me insight into the running of an art studio and how it functioned as a whole. It also made me realize my priorities, both professionally and emotionally. I learned to appreciate and enjoy the day-to-day process and take nothing for granted. Robert was never really happy, no matter how successful he became. It was never enough. I sat for Robert a few times as I did for many art photographers in the city. I was also a fashion model for a while. Being in front of the camera gave me a unique perspective that was helpful in making subjects more at ease when I was behind the camera as a photographer.

Luntz – What were you exploring with your early photographic self-portrait work? How do you think it fits into your evolution as an artist?

Leatherdale – Self-portraiture was an exploration that I think all artists dabble in. This was not as the “selfie” which is merely an instant, self-centered and vapid form of egotism. My self-portraits were more about what I felt, not what I looked like.

Luntz – Tell us about your series “Hidden Identities” taken in New York City in the 1980s.

Leatherdale – “Hidden Identities” started at a DaDa Night in a nightclub called Underground. Different participants settled themselves up in different areas of the club. I took over the go-go cage and was photographing unidentifiable portraits as a form of Dada expression. Shortly afterwards, Stephen Saban and Annie Flanders started up Details magazine. Stephen approached me to do a monthly page of these portraits and actually came up with the name “Hidden Identities.” It started with these portraits, but then expanded to photographing the who’s who of downtown cool. The series ran for several years and was not a commercial gig at all. I was given total freedom to choose anyone I wanted. I loved doing it.

Luntz – How did observing and documenting the decadent and fashionable world of 1980s New York City affect your subsequent work making portraits of native people in India?

Leatherdale – I did not observe the scene of the 1980’s; I was actually a part of it. That’s what I feel gives that body of work the clarity and insight that documentary and paparazzi photography lacks. I was a part of “the in crowd.” However, I did not totally realize at the time that I was archiving an era that would be extinct in twenty years. We thought we would be twenty-something forever.

Luntz – When did you first arrive in India and what originally drew you to relocate there?

Leatherdale – I first travelled to India in 1972 arriving cross-country in a Dutch hippy van. We drove from Istanbul through Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan to India. I was seeing the world before college and wandered about the country for several months before returning the same route (but without the Dutch hippies) to Europe. Then I went back to Canada and finally on to California for art college. In the late 1980s I returned for a one-month vacation. I realized then that I really wanted to photograph in India, but as a professional studio photographer, not as a tourist with a 35mm camera. I returned to New York City where I was then based and organized an expedition trip with producer and writer James Killough. We returned as guests of the Indian government. We traveled with a portable studio in a Matador Van with a driver and assistant for three months. We drove all over India: north to south, east to west. This was the start of my life’s work in India. I never took another photograph outside of India again.

Luntz – You were then based in the city of Banaras (Varanasi) where your first studio was located. What about that city intrigues you?

Leatherdale – After my three-month expedition, it only increased my interest to work more in India. My New York City gallery also encouraged me to continue, as the work was well received and selling.

But I wanted to be based in a studio this time, rather than bumping about the country in a location studio van, which can be quite exhausting. I decided to base myself in Banaras and create a rooftop studio in an old Haveli (townhouse). Banaras is a pilgrim destination where all Hindus, at some point, make a pilgrimage. It’s situated on the sacred River Ganga and is the ultimate place to die or be cremated. I figured I could just stay put this time and let India come to me.

Luntz – Are there particular types of people that you seek to photograph in India?

Leatherdale – I worked in the Banaras studio for several years spending up to half the year photographing traditional Hindu life, mostly pilgrims and Sadhus (holy people). At first it was the diverse traditional aspect of India that intrigued me. I was also photographing everyone from Maharajas to temple beggars, fishermen to yogis. However on my previous expedition, I encountered the Adivasis people. They are the tribal people of India, the so-called “first dwellers.” I promised myself that I would focus on these tribes once I was more settled in India. In 2000 I relocated to the tribal state of Jharkhand. I am still based there and work exclusively with the Adivasis. It’s a good central location to branch out in expeditions to photograph all the tribals in India. Aside from the state of Hariyana, there are Adivasis in every state, so this does and will take a fair amount of travel within India. I have a Mahindra Jeep called “Hara Hati” which means Green Elephant. My estate manager, Kailash, travels with me on all my expeditions and has been with me since Banaras. He and his wife look after me and I look after them. It is a give and take arrangement and I could not be based in India without his loyal efforts.

Luntz – What is your process in finding and then approaching them for your portraits?

Leatherdale – As you now know, I am totally focused on the Adivasiss of India. I have to research all the possibilities such as which ones are the most untouched traditional tribes and where are they are located. I research how safe the political climates are and how accessible their villages are. I usually approach local NGOs and missionaries in the interested area which deal with the Adivasis. From there I can usually find tribal members that are working outside and then will bring me to their village and introduce me to their elders. I explain that I am paying homage to the tribals of India and I say, “How can I not include your tribe as well?” That always works. I then schedule the next morning because I have only from 8 to 11 AM to shoot in ideal light. I also encourage the villagers not to go out working or hunting, as I will pay them each a day’s wage when I photograph them. I also bring in 50 kilos of rice and arrange for medical aid if necessary.

Luntz – Do you sometimes set up your camera and background around where the people are located or do you always have them come back to your studio?

Leatherdale – When I was based in Banaras, I had a permanent studio set up on the roof of my Haveli and an assistant would bring subjects in the mornings. Now being based in Jharkhand in a forest bungalow, I have to organize specific expeditions which usually last two to three weeks. I bring a black canvas backdrop and a white cotton canopy tent. The tent is supported with bamboo poles and held up by two of the locals. The backdrop is somehow fixed to a flat vertical surface under the canopy. It can be a bit of a circus because the whole village comes out to watch. Sometimes I even have to hire a few Adivasiss to help with crowd control, which is never serious but can get a little rowdy.

Luntz – What kind of camera do you use? Can you comment on your split-tone printing technique?

Leatherdale – I use a Hasselblad and negative film, no digital equipment. My intention is to have a timeless quality to my work, so it seems senseless to use digital imagery. My split-toned prints come from wanting my photographs to be timeless. It makes you wonder if the images are 19th, 20th, or 21st century? Pure sepia tone is too orange and too faded for my liking, so I only bleach out the highlights, not the shadows. When I tone the print with sepia toner I get deep and rich dark browns.

Luntz – Do you aim to connect with the subject or do you maintain a distance? Is it important for you to show your sitter’s personality and distinctiveness in your work?

Leatherdale – Of course I want to connect with my subjects. My first influences with Indian portraiture were the old Raj images of the 17th and 18th centuries. The British photographers were too removed and distant from their subjects. They were almost specimen shots. I want to show the timeless tradition of India, but also the personality of the sitter.

Luntz – Do you think it’s important to document the Adivasis for posterity? Do you view your work as anthropological documentation?

Leatherdale – Absolutely. In the not so distant future, tribals will no longer be living traditionally as their ancestors have for eons. They are being morphed into the global village society of our modern world. Baseball hats and cell phones are turning up everywhere. I want to reserve the tradition of these proud people as best I can, somewhat like Edward Curtis did with the American Indians. My work can be viewed as anthropological portraiture, even the vintage New York City work of the 1980s. They are just different tribes and both are now obscure. However, my photographs are too poetic and personal to be labeled as purely documentary.

Luntz – Do you believe over time since you first went to India that you’re more connected to the Indian people? Do you have many frustrations working there?

Leatherdale – I have a love-hate relationship with India. It’s like a rocky love affair. I miss India terribly when I am “out of station” and cannot wait to go back. Then after four or five months of being in India, I cannot wait to leave. India can be extremely frustrating and the heat can be intolerable. Having said that, it is also the most magical world I know. I have experienced the most beautiful moments of my life in India. I am called “Adha Hindustani” (half-Indian), but after all these years I still never know quite what to expect, nor how to deal with what may be around the next corner. There is no autopilot or cruise control in India. This uncertainty keeps me young and impressionable. India is my other side of the looking glass.

Luntz – What do you hope people appreciate when they look at your work?

Leatherdale – Perhaps I hope they enjoy the pleasure of looking at something beautiful and unexpected. I also hope there’s a touch of time travel into a parallel world that actually still exists as we speak.

Luntz – What are you working on these days? Are you involved with any charitable causes in India?

Leatherdale – I am still photographing the tribals of India and will continue to do so. It’s my life’s mission to capture the traditional Adivasiss before they disappear and become only a memory. Tradition has sadly become “old school.”

Ilona Ghosh, Amit Ghosh, Jorge Serio, and I started up the MCT (Medical Care Team) in 2000. It was our personal karmic pay back project, which involved free medical aid from tuberculosis medication to cleft palate operations. We organized cataract eye camps and women’s camps with female doctors who could examine for breast cancer. Recently due to personal circumstances, Ilona and Amit moved away, we have had to reduce our focus to having a doctor‘s office in the back of the local medicine shop. They will examine patients and offer medicine for whatever they can afford or for free depending on the patient’s situation. We do what we can. India has given me so much that I feel I have to give back.

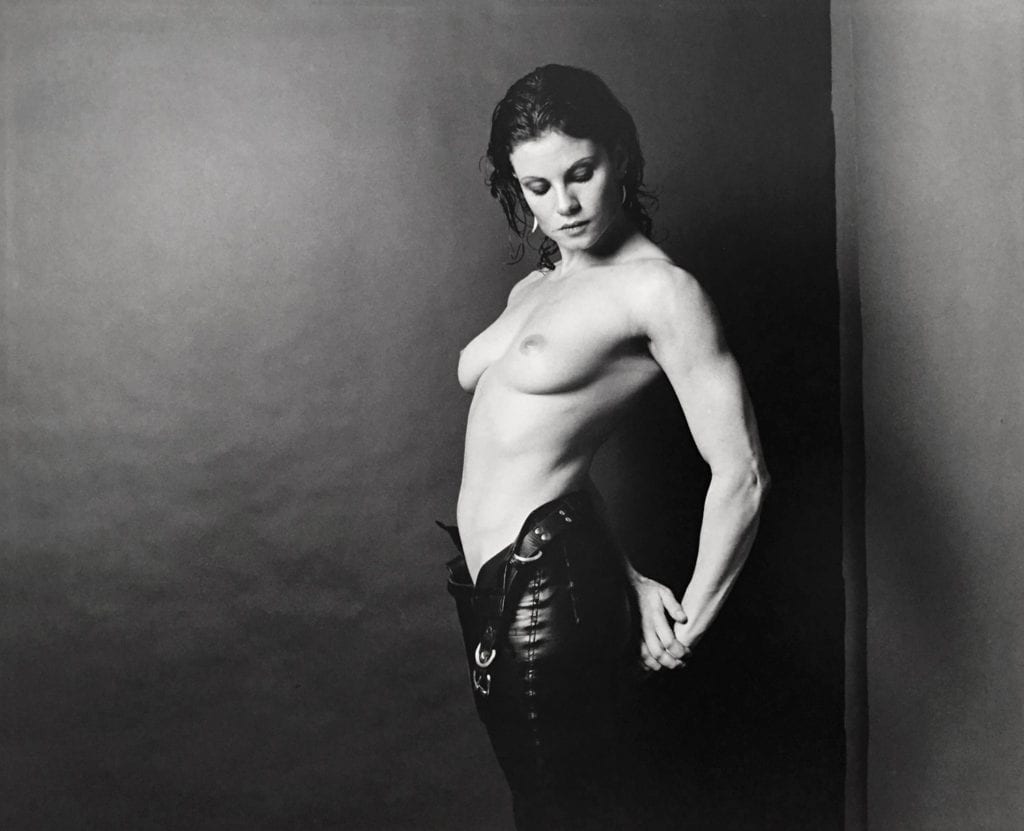

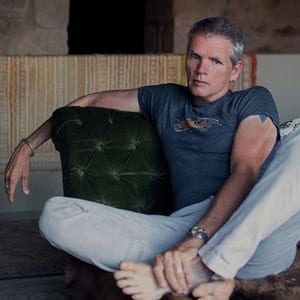

Marcus Leatherdale was born in Canada and started his career in New York City during the early eighties. Having become one of the extraordinary people of the vibrant club scene of Danceteria and Club 57, he created portraits that encapsulated the New York lifestyle of such individuals as Madonna, Divine, Lisa Lyon, Andrée Putman, Jodie Foster and fellow photographer John Dugdale.

Marcus Leatherdale was born in Canada and started his career in New York City during the early eighties. Having become one of the extraordinary people of the vibrant club scene of Danceteria and Club 57, he created portraits that encapsulated the New York lifestyle of such individuals as Madonna, Divine, Lisa Lyon, Andrée Putman, Jodie Foster and fellow photographer John Dugdale.

He first served as Robert Mapplethorpe’s office manager for a while and was photographed by the master but eventually escaped his shadow; thereafter he worked as an assistant curator to Sam Wagstaff. He had his work published in Interview, Details, The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and Elle Decor among others. Later on he was featured in art publications such as Artforum, Art News, and Art in America. International recognition paved his way to museums and permanent collections such as the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Australian National Gallery in Canberra, the London Museum in Ontario and Austria’s Albertina.

In 1993, Leatherdale began spending half of each year in India’s holy city of Banaras. Based in an ancient house in the centre of the old city, he began photographing the diverse and remarkable people there, from the holy men to celebrities, from royalty to tribals, carefully negotiating his way among some of India’s most elusive figures to make his portraits. From the outset, his intention was to pay homage to the timeless spirit of India through a highly specific portrayal of its individuals. Leatherdale explores how essentially unaffected much of the country has been by the passage of time; this approach is distinctly post-colonial. In 1999, Leatherdale relocated to Chottanagpur (Jharkhand) where he has been focusing on the Adivasis. His second home base is now Serra da Estrela in the mountains of central Portugal.