Explore the intricate relationship between humanity and nature through the lens of Francesca Piqueras in this insightful interview. Delve into her exploration of environmental themes and the transformative power of man’s interaction with the landscape. Discover how her work navigates the delicate balance between aesthetic pursuit and political commentary, inviting viewers to contemplate the beauty and complexity of the world around us.

Luntz – What is the continuous environmental message you want to talk about in the various bodies or work? And are there underlying conditions linking them all?

Piqueras – There is a very direct link between all of my series and the environment. It is definitely about the influence of man on the landscape, on its environment, on nature, on its vital space. Man builds for energetic or economic reasons. He transforms the landscape with what he sows and abandons to build elsewhere.

He is a predator.

Nature digests his excesses, decomposes them over time, with difficulty, and gives them life again under different shapes, slowly but surely.

This juncture is where I intervene, in this metamorphosis, this transformation, which is almost a transmutation. What I am interested in is what man builds in his environment, e.g., what he does with it, so this is, in effect, an environmental theme in the sociological sense rather than the biological, even though for me, the aesthetic part is more important than the ideology.

Luntz – Would you say that your work is essentially about our relationship to nature?

Piqueras – My work is, as I said, fundamentally focused on the relationship of man to his or her environment, in which nature takes a huge part, and the contrast is even more blatant. But my work is more and more keyed to matter, to the elements because, as decomposition and re-composition are my main topic, structures or elements of structures turn into matter, and I focus more and more of my photographs on this aspect, on this aesthetic.

In focusing more and more towards this aspect, my photographs lean more and more towards an abstract form.

Luntz – Photography is a static form of capturing an image. Is it a big challenge when you want to show movement?

Piqueras – It is fascinating. You must capture the dance, the energy from where movement originates and where it ends. This is absolutely pictural. It is a work that pushes the eye beyond the obvious, which perfectly expresses the tensions of the wounds that man inflicts upon nature or the energy liberated by human intervention. It is this movement of back and forth, of inner dynamics between man and the elements, which is at the core of my work.

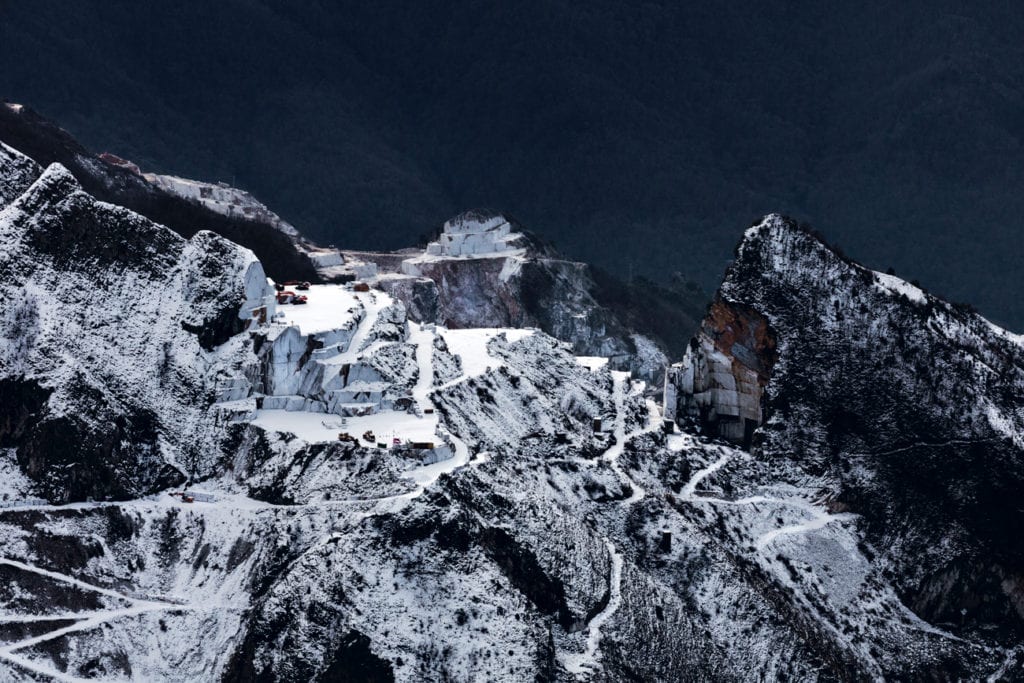

Luntz – I think that your work is essentially about our relationship with nature. In what sense are we or nature the destructor? We seem to want to harness nature – whether through mining for marble, converting matter through the use of fire, building huge tankers to cross the Ocean, drilling for oil in the Ocean, diverting bodies of water for hydroelectric power. Do you see these as essential struggles?

Piqueras – It is a paradoxical and essential struggle. In all you just mentioned, man intervenes very often out of necessity. But I feel that this mistreatment of nature, of the environment by man – and this is where the paradox is – comes from the fact that man does not consider his environment as an ally, but as a foe, a stranger he needs to fight and subdue at all costs, without caring for consequences. In reality, man burns the very land he stands on, and it is a lost fight for him.

In my work, I do not judge. I interpret with my tools, light and framing. Drama is here anyway. Strangely, this drama also bears life and hope, as it carries a certain romanticism, a little like the painting storms of Turner or the ruins of Hubert Robert.

One can feel certain states of mind exacerbating this struggle. I have to admit I am fascinated by this fight. It is the expression of the best and the worst of human beings.

Luntz – Mankind vs. nature is thematic in your work – yet we never see humankind in the person – only the evidence of its attempts to control nature? Does this make the work impersonal?

Piqueras – I chose deliberately to do an artistic work that would not be documentary but would lean towards a narrative that suggests but does not show, which does not illustrate, I am here as I said to interpret, so man is always present, but I do not feel necessary to show him! To leave man aside in simply suggesting his presence through the energy he puts into play, is for me, something stronger when I tackle a project.

Luntz – Your work deals with the elements water, air, fire. Have these always been your concerns?

Piqueras – Always. I deeply love each of these elements. I like to combine matters. I do it in my diptychs as a dialogue between them. I will most probably confront a photograph and a sculpture whose matter will be present in the image, a sculpture that will stand eye to eye with the photograph.

There is in the elements something that symbolizes freedom as I figured it was when I was a child. In my solitary wanderings – because I was a very solitary child – I closely watched the earth, the matters on fire, fire in my father’s sculptures.

I think that, if you are an artist, there cannot be sincere work if you are not looking into what resonates within you, that you can project onto a theme that is both universal, elementary, fundamental, which concerns us all. It may be there that emotion appears in a work of art if, of course, one wants to make an artwork that carries emotion.

Luntz – How do you go about researching your shoots? How long do they usually take?

Piqueras – I am lucky enough to exhibit a solo show once a year so that I can confront my work with the audience’s point of view. I am lucky to observe it, and this is where I find the answer when it comes to the next project. Then, it takes a minimum of one year to find the spot, organizing the logistics and the actual work. I now live in Italy, surrounded by matter: marble, water, and so on… It is a laboratory!

Luntz – What is the significance of scale – or the size of your prints in your work?

Piqueras – It is very important to me that images carry a certain dimension in order to give the scale of the monumental: What I photograph is most of the time both immense and very expressive. You must sense it, perceive it. You must feel yourself physically touched. In a large print, you get a more direct access to emotions, dramas, matter. You almost physically get into the image.

Luntz – Do you see yourself influenced by any other photographers? Do you link your work to any other photographers?

Piqueras – No, I feel influenced by painting. Being the daughter of a painter and a sculptor, I have been terribly influenced by this medium. In a painting, you have to look beyond what is shown. You must seek for the discourse of the artist.

It is like writing. There is, for whoever watches artwork or reads a book, a very important creative process where the artist or the writer suggests and where the reading of the work implies the viewer’s history, their past, their culture, their traumas, and personal references. It is the viewer who imagines and projects what they see or read.

Luntz – It is often hard to judge scale in your work. The Ocean – the quarries, the tankers – the drilling stations are massive – We, as individuals, are dwarfed. What made you want to concentrate on the ‘macro’ image?

Piqueras – The scale of the immensity of the elements or the structures that I photograph, the paradox of the vulnerability of man and the power of its destruction. The colossal size of the structures suggests man’s power and ingenuity, and when I show abandonment, his destructive power, his vulnerability is suggested.

It is within this scale that I feel the conflict between man and nature is best expressed.

Luntz – Do you have a political voice that wants to say something in your work? Or is the aesthetic pursuit your goal?

Piqueras – Since I photograph man’s intervention, there is obviously a political stance if you define politics as the organization of a social group, which may imply negative or positive forces at play, depending on the point of view.

I am more attached to aestheticism in the sense of beauty, emotion, senses, feelings. But my aestheticism is not opposed to thinking, to a reflection or a standpoint. This is not a reduction of thought, where beauty would annihilate conflict, violence, contradiction. It is not a reductive aestheticism, rather an expressive and sensitive, powerful and visual one.

Luntz – How has your work evolved over the last decade? Are improved digital cameras impacting your work?

Piqueras – Compared to my first camera, yes, the definition is much better. But I do not want to sterilize my work through photographs too technically perfect, which, I feel, creates a distance, and this is not what I am aiming for. Certain defects do not bother me, and they will always exist, considering the way I work.

I put the emphasis on the atmosphere. Which, to me, implies an almost permanent underexposure, which in turn brings imperfections… they are my friends.

Francesca Piqueras grew up in a family of artists. Her parents were close to artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray or Salvador Dali and she would often see them in summer, in Cadaques.

Francesca Piqueras grew up in a family of artists. Her parents were close to artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray or Salvador Dali and she would often see them in summer, in Cadaques.

In this artistic milieu, she grew up as a solitary and attentive observer. At the age of ten, she discovered her passion for making videos and was offered a camera she receives as a gift. She studied art history and cinema, and worked as an editor, without abandoning her passion for photography and cinema.

She presented her black and white photographs for the first time in 2007. Her first series focused on an urban world, magnifying human traces that can often be seen in the city.

Marked by Michelangelo Antonioni’s “Il Deserto Rosso”, her interest is focused on a different type of traces: those of our industrial civilization. She switches to color photography and presents new works in 2011, “The Architecture of the Absence”, a series taken on sites of boats dismantling of ships in Bangladesh, and, in 2012, “The Architecture of Silence”, with photos of freighters scuttling in Mauritania. She pursues this artistic project between sea, sky, metal and rust through her interest in oil and military platforms.

“I photograph what man builds for economic reasons or for wars. Men invented incredible structures to satisfy their needs. They build in extreme situations, and in a way which may be questionable. But my point is not to denounce. On the contrary the madness of man, his paradoxes and contradictions interest me. The climax of the aesthetics of these objects is for me when nature takes them over. Time, rust and decay transform these architectures into sculptures and rewrite, poetically, the history of man. Our history.”

Today the artist works on several other projects about industrial relics all over the world.