Transcription in progress

The Intimacy of Seeing: A Conversation with Jean-Baptiste Huynh

For more than two decades, Holden Luntz Gallery has presented the work of Jean-Baptiste Huynh — an artist whose practice spans continents yet remains formally disciplined and philosophically precise. At the opening of The Intimacy of Seeing, Luntz and Huynh reflected on portraiture, light, identity, and the pursuit of essence across cultures.

What emerged was not a survey of geography, but a sustained inquiry into presence.

Vietnam: Returning to the Origin

Holden Luntz: “Jean-Baptiste asked that we begin with Vietnam. And that’s essential, because this is not just where the work begins geographically — it’s where the inquiry begins.”

“When we look at Japan, India, Mali, Ethiopia — the formal language is already there in Vietnam. The black background. The square format. The single light. But the motivation is deeply personal.”

Jean-Baptiste Huynh: “I am half French and half Vietnamese. I was born in France. My mother was French, my father Vietnamese. I grew up surrounded by European faces — round eyes, white skin, curly hair. I did not see my own features reflected around me.”

“I wanted to understand the origin of my face.”

In 1996, Huynh traveled to Vietnam not to document the country, but to study the Vietnamese face across age.

“The idea was to photograph from young children to older people — to see how the features evolve. How identity changes through time.”

One young girl became central to the project. He first photographed her at eleven and returned repeatedly over decades.

Huynh: “I have her at eleven, twelve, fifteen, twenty, thirty. You can see the transformation. Childhood becomes adolescence. Adolescence becomes adulthood. The face records it.”

Luntz: “You weren’t just photographing individuals. You were constructing a study — almost a typology.”

Huynh: “Yes. I wanted to understand the structure of the face.”

From the beginning, context was removed.

“I isolate the person from social environment. When there is nothing around them, you are only facing the person.”

Vietnam established the grammar of the work: square format, black ground, singular illumination, direct encounter.

Everything that followed grew from this foundation.

Japan: Discipline and Silence

Luntz: “After Vietnam, you continued your study of the face in Japan. The formal language is already established — the square format, the black background, the single light — but something shifts psychologically.”

“There’s a restraint in the Japan portraits. A composure.”

Huynh: “Yes. In Japan I was very interested in silence.”

“The face there is very interior. It is not expressive in an obvious way. It is contained.”

Huynh continued the same method he began in Vietnam: isolating the subject from context, eliminating environment, focusing only on presence.

“What interests me is not expression in the theatrical sense. It is something quieter. Something before we decide how we want to be seen.”

In Japan, he was also drawn to symbols embedded within the culture, including calligraphy and gesture.

“I like to photograph symbols of culture — but always in the same way. Isolated. With the same light.”

Luntz: “You could feel the discipline sharpening. The work became even more distilled.”

The Japan portraits do not project outward. They hold themselves inward. The intensity is not dramatic — it is controlled.

Huynh: “For me, it is the same research. The face. The structure. The presence.”

The Square Format and the Discipline of Light

Huynh has used the same Hasselblad camera and lens since he was seventeen.

Huynh: “My teacher believed in me. He lent me money to buy my first camera. I still use it.”

The square format has remained constant.

“In nature, nothing is square. That is why it is powerful. There is one center. It is calm.”

The square eliminates hierarchy. It does not privilege height over width. It stabilizes the subject.

He works with one light.

“I choose the direction of the face and the direction of the light. After that, I don’t look at the camera. It becomes something between the person and me.”

Luntz: “There’s a perfectionism in that restraint. Nothing is decorative. Nothing is excessive.”

The discipline — one camera, one lens, one light — becomes generative rather than limiting. Within it, infinite variation unfolds.

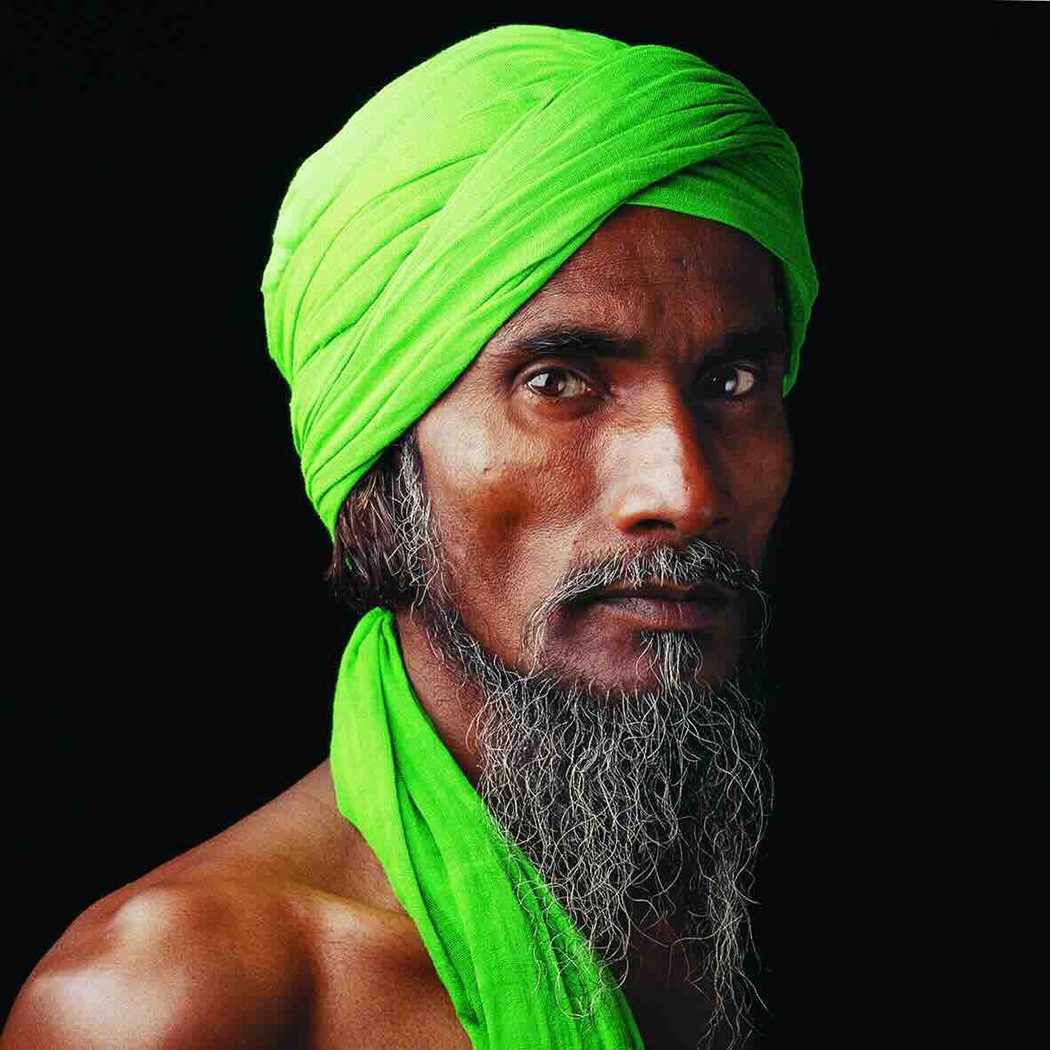

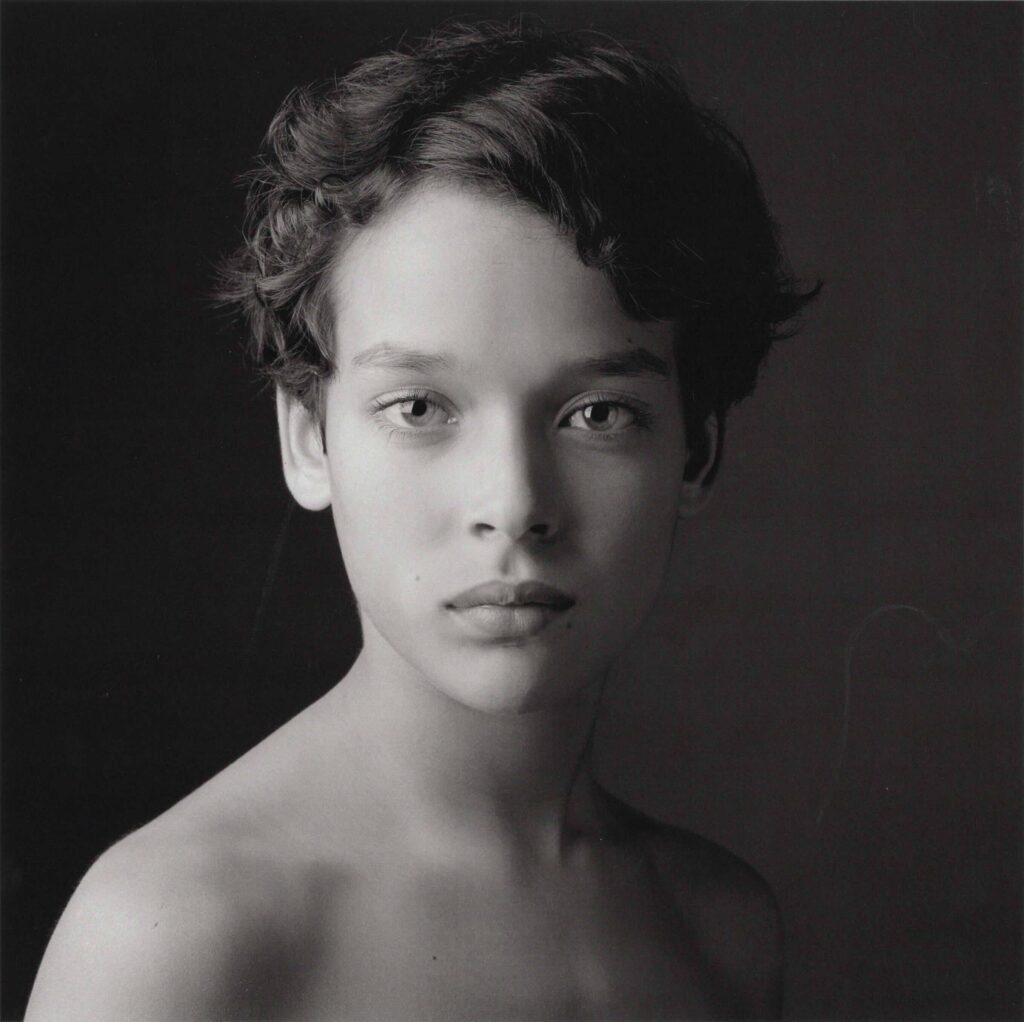

India: The Image That Endures

As portraits from India appeared, Luntz reflected on their early reception.

Luntz: “When we first showed Jean-Baptiste’s work at an art fair in Palm Beach, people walked into the booth and simply stopped. Museum directors, foundations, collectors — there was no need for explanation.”

He referenced a portrait of a young boy from India.

“My wife Jodi saw this image and put a red dot on it. She said, ‘We’re keeping this.’ It hangs in the front hall of our home. Every day I look at it. It never loses its power.”

“There is strength in that face. Vulnerability. Dignity. The light feels internal.”

Huynh: “He was coming from a game. I set up my small studio. It was very intense.”

Luntz: “What’s remarkable is that there’s no performance. He isn’t posing. He simply is.”

Huynh: “I don’t ask for expression. I place the person in the light. After that, it becomes something between us.”

The portrait remains open. It does not resolve itself. It deepens over time.

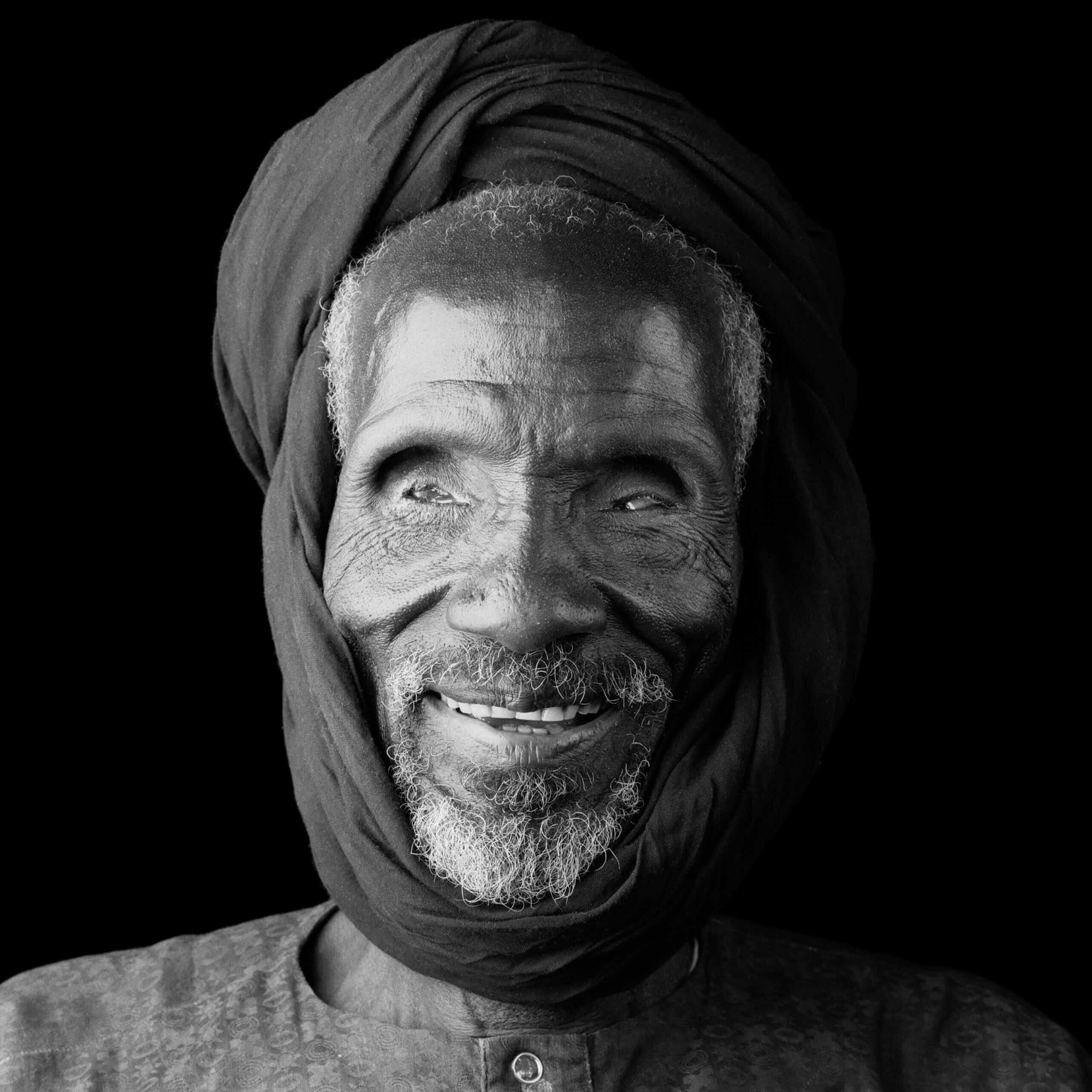

Mali: Identity Across Cultures

Luntz: “When we began representing you more than twenty years ago, some of the first bodies of work we showed were Mali, Ethiopia, Japan, and India.”

“And what struck me immediately in the Mali portraits was that the formal language hadn’t changed at all. The black background. The square format. The single light. But the cultural shift was enormous.”

“There was a cross-cultural search happening.”

Huynh: “After Asia, I wanted to move to Africa. It was a big challenge for me.”

“In Mali, I was discovering faces that were very different structurally. The intensity was very strong.”

Huynh approached Mali with the same discipline he had applied in Vietnam and Japan.

“I always photograph one face, in front of a black background. I like to isolate the person from social context.”

Without environmental detail, the portrait is no longer documentary. It becomes elemental.

Luntz: “When you look at these portraits, the sense of calmness and serenity is extraordinary. And yet you had often just arrived. You didn’t speak the language.”

“How do you establish trust in that moment?”

Huynh: “I use my face as a mirror.”

“If I smile, they smile. If I relax, they relax. It is not about speaking. It is about sharing something.”

Mali marked a deepening of Huynh’s inquiry. If Vietnam began as a search for personal origin, Mali expanded that search outward.

“I wanted to understand the face through different cultures,” he said. “But the inside is the same.”

Luntz: “The faces are different. The bone structure, the features, the light on the skin. But the presence — that remains constant.”

In Mali, the work became unmistakably universal.

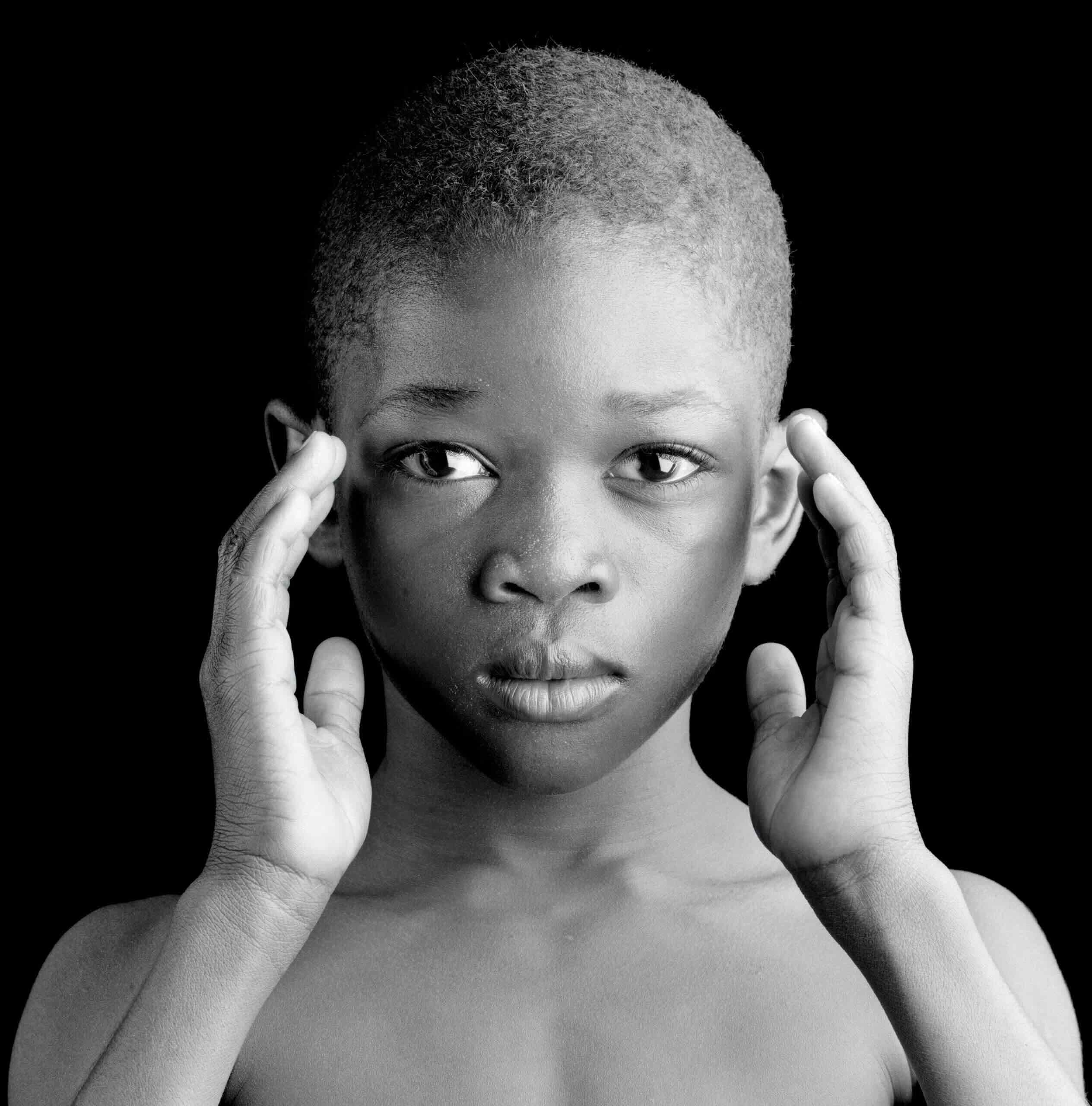

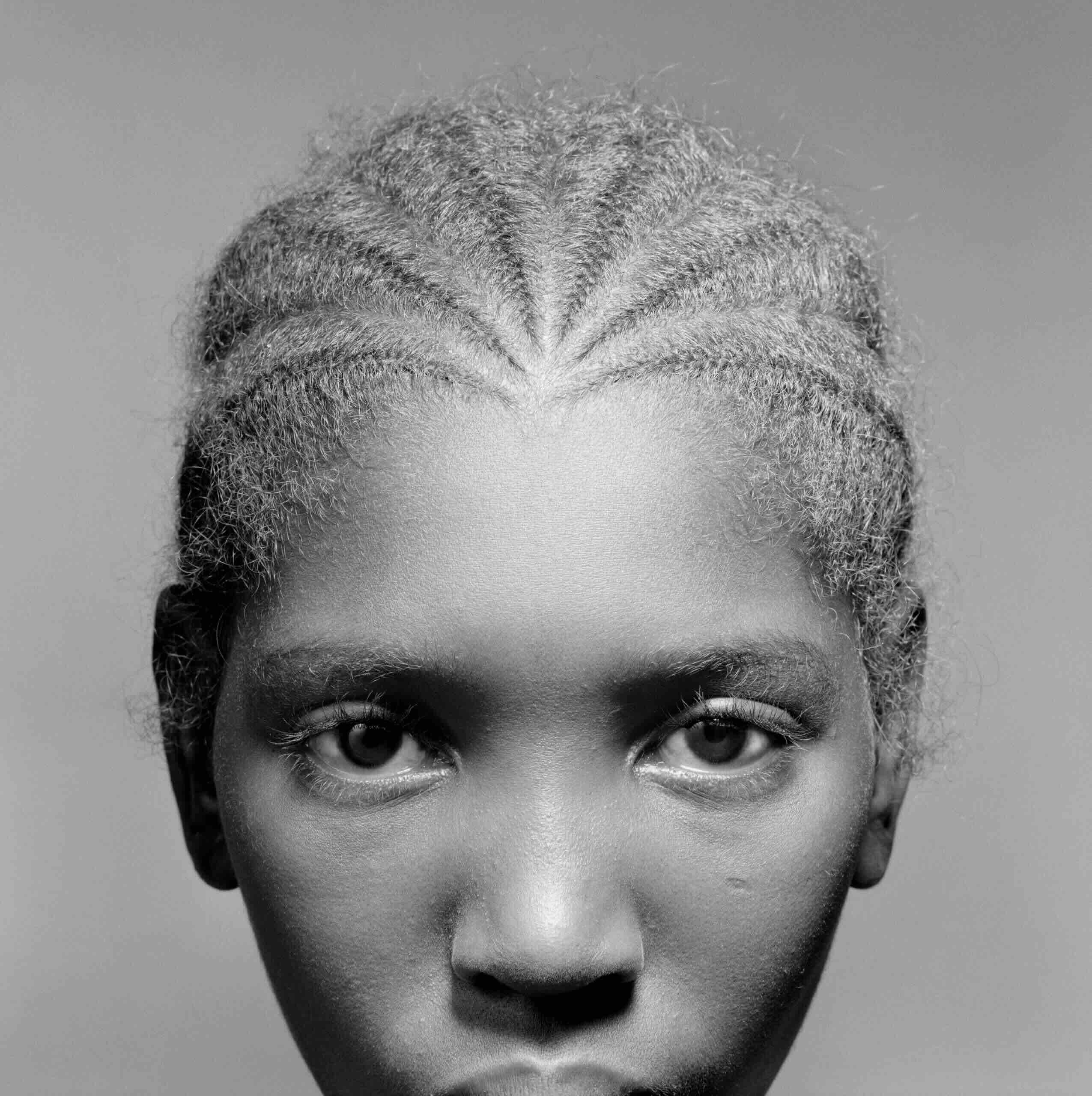

Africa: Presence Without Language

When the images shifted to Mali and Ethiopia, the intensity sharpened.

Luntz: “There’s something architectural about these faces. The structure. The bone. The gaze.”

Huynh: “It was a shock for me. A very strong shock.”

Language was often absent.

Luntz: “How do you build trust when you cannot communicate verbally?”

Huynh: “I use my face as a mirror. I smile. I soften my expression. It is not verbal. It is something felt.”

He returned to a recurring theme.

“When people look at themselves in a mirror, they change their face. Everyone tries to control their image.”

Children, he explained, do not.

“They are not yet self-conscious.”

Animals, too.

“They know who they are. They do not pretend.”

Across cultures, the pursuit remained consistent: to reach a moment before performance.

Twilight: The Threshold of Light

Light, present in every portrait, became the explicit subject in the Twilight series.

Luntz: “There is something almost spiritual about these works.”

Huynh: “When I was a child, my mother would take me to the roof at dusk. She would say, ‘Jean, look. God is writing with light the line between day and night.’”

Years later, Huynh photographed twilight at observatories across the world, including the Paranal Observatory in Chile.

“There is no humidity there. During the day it is warm; at night it is minus twenty-five degrees.”

“Twilight is a door. Between day and night. Between what we see and what we cannot see.”

During that narrow interval, the sky reveals what daylight conceals. The Earth’s shadow becomes visible. The stars emerge before darkness fully settles.

“People think night is when light disappears,” he said. “But twilight shows that light transforms.”

Light is not embellishment. It is structure. It is subject.

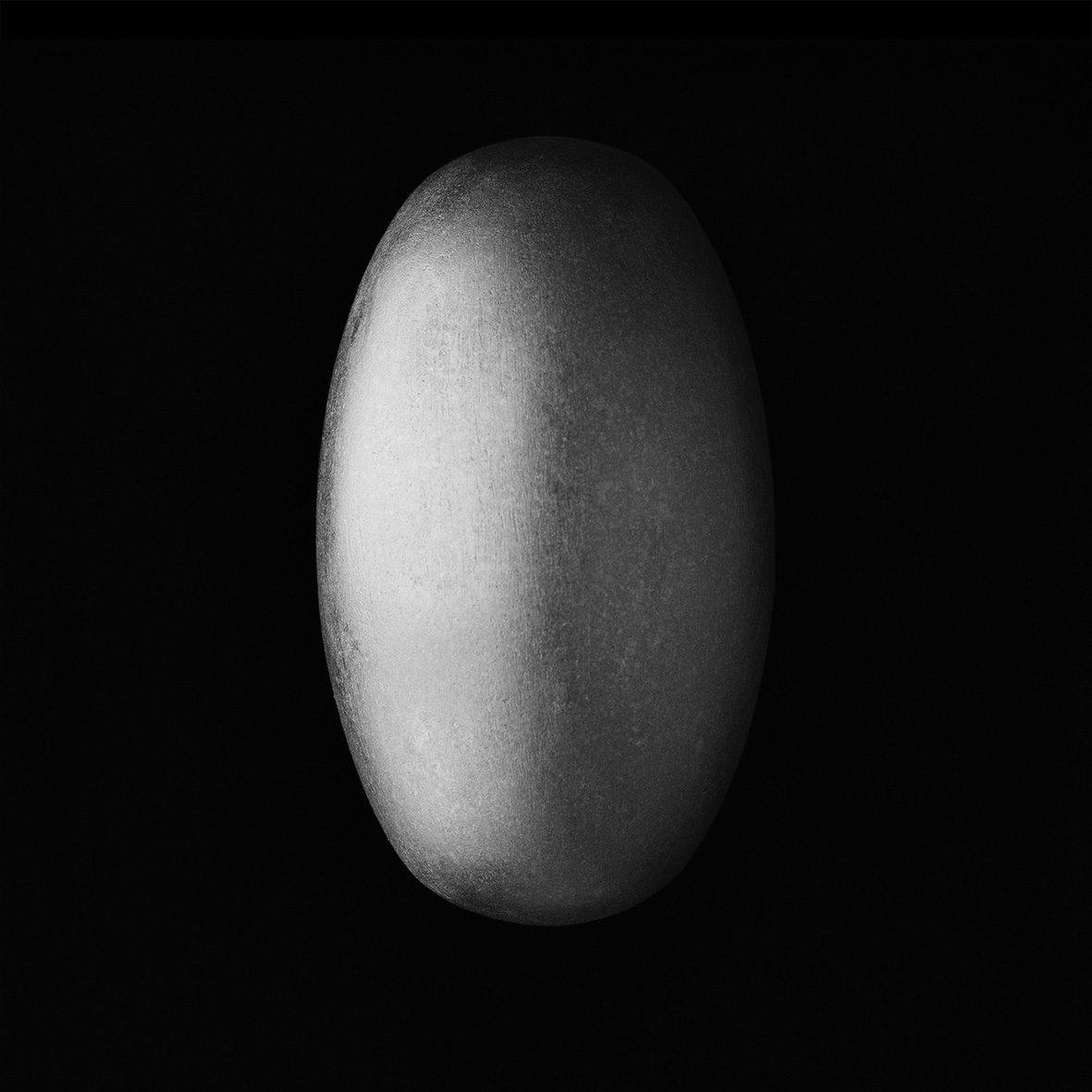

Mirrors: Reflection and Absence

After a major retrospective of his portrait work, Huynh turned toward ancient mirrors from Egyptian, Roman, and Asian civilizations.

“Our image does not belong to us,” he said. “We see our face only through reflection — and even then, it is reversed.”

Many of the mirrors he photographed had oxidized surfaces that no longer reflected clearly.

“I was fascinated by mirrors that do not reflect anymore. If the image disappears, what remains?”

Luntz: “It’s the same inquiry as the portraits — but without the face.”

Huynh: “Yes. It is still about identity.”

Hands: A Portrait Without the Face

One of Huynh’s earliest published projects focused entirely on hands.

Luntz: “One of your first books was hands. And they function almost like portraits.”

Huynh: “I like to photograph hands because they are the only sense that is not on the face.”

“All the other senses — sight, smell, taste, hearing — are here.”

He gestured toward his face.

“But hands… hands tell something different.”

For Huynh, hands hold biography. Labor. Age. Gesture. Character.

“They reveal the person without the face.”

Like the portraits, the hands are isolated against black. The square format remains. The light remains singular and directional.

Nothing decorative. Nothing sentimental.

Just structure. Skin. Tension. Bone.

Luntz: “There’s something architectural about them. They feel sculptural.”

Huynh nodded.

“It is the same approach as portrait. You look at the hand long enough, and you begin to understand the person.”

One image in the series became a book cover. It is also one of the few works that was ever slightly cropped from its original square — though originally conceived within that disciplined format.

Even here, the investigation remains consistent: form as identity.

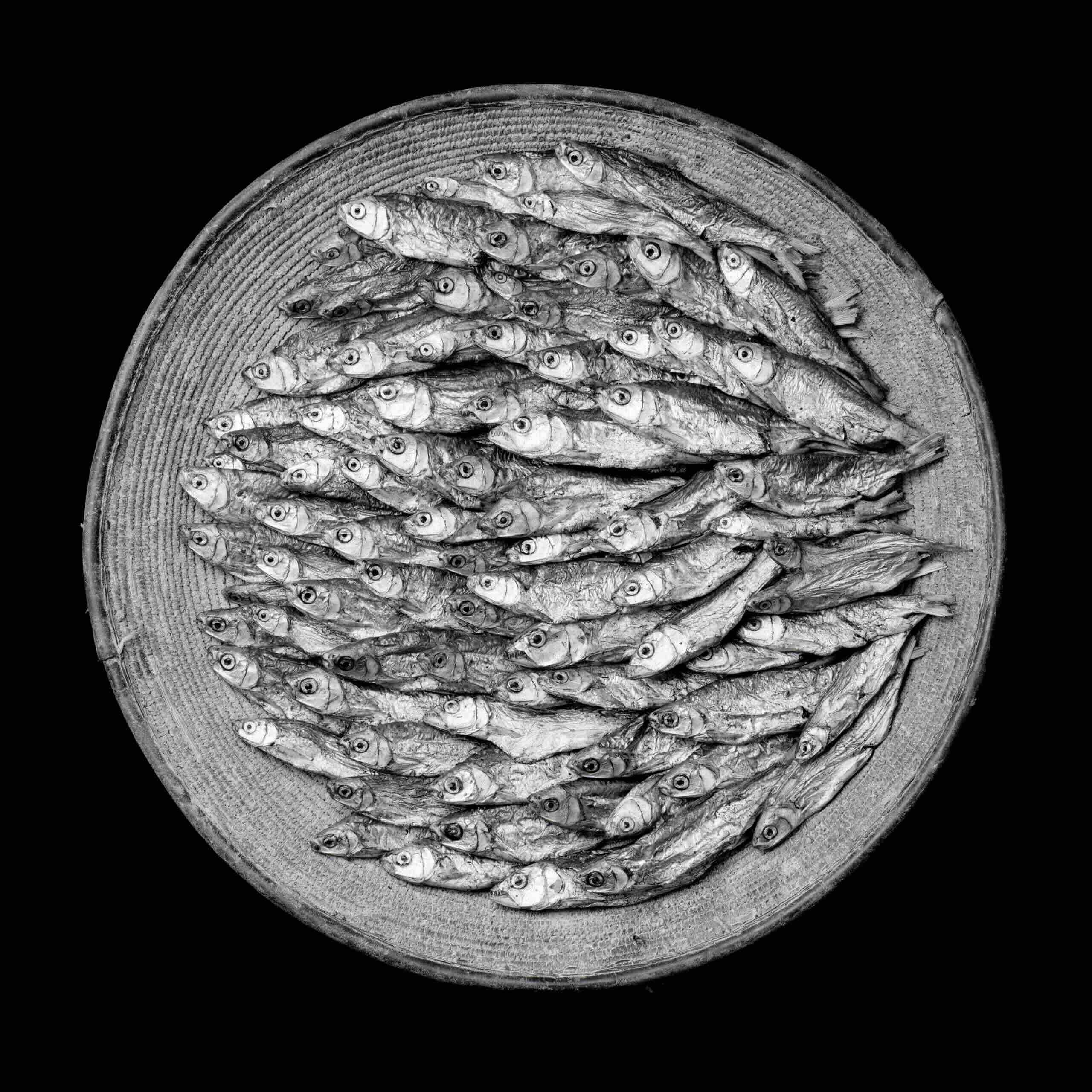

Nature and Still Life: Form as Essence

Huynh’s still lifes and botanical works extend portraiture into another register: the face becomes flower, the gaze becomes surface, the encounter becomes form.

Luntz: “You talk about nature as if it has the same kind of soul and substance that a person does. The same square format. The same unadulterated background.”

He referenced a still life with a French title, often translated as “Love in the Cage.”

Huynh: “I did that one in Vietnam. Everywhere I go, I set up a little studio near the market. I go to the market and choose what I will photograph.”

The challenge is not selection but illumination.

“It is a challenge to light it. To give it dimension. To place it in the context of the picture plane. It is not one bud, not one small object. It is form.”

His control of light—learned through decades of using a single flash—allows a precision that feels effortless.

“I know this light perfectly,” he said. “I know where the shadow will be.”

Nudes: The Architecture of the Body

Luntz: “We have nudes in the back room. They are sensual, but they aren’t sexual. They are expressions of form.”

Huynh: “I’ve been photographing nudes for thirty years. I am interested in the architecture of the body, the sensuality of the skin, the form itself.”

He described the nude not as a separate category, but as continuity with nature.

“It is very close to the work I do on nature. It is about form and how I can light it.”

The body becomes landscape. Light becomes structure.

Fire: Light That Cannot Be Controlled

Fire introduces a different problem: a subject that resists intervention.

Huynh: “You cannot light fire. Fire lights itself. If you use flash, the flame disappears.”

Flame moves faster than intention.

“It is so fast. It changes constantly.”

Candlelight is even more delicate.

“Even a breath several meters away will move the flame.”

The fire works demand a different kind of discipline: not control, but respect for the autonomy of light.

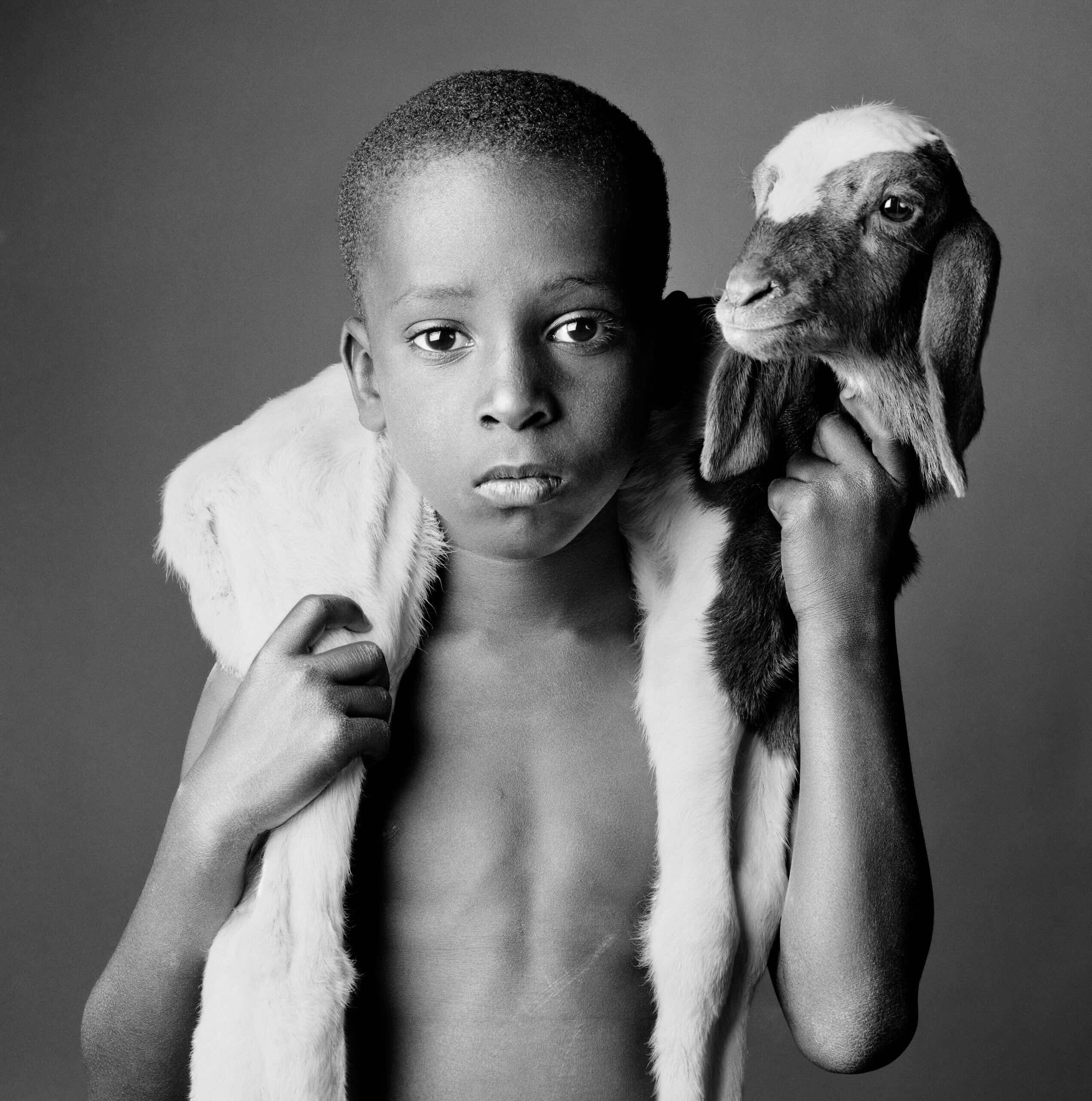

Animals: The Absence of Image

Animals extend Huynh’s portrait inquiry: presence without performance.

Luntz: “Is it the same with animals as with children?”

Huynh: “Yes. Animals do not try to build an image. They know who they are.”

He speaks to them—not for language, but for tone.

“Even if they don’t understand the words, they understand the sound, the tone of my voice. It is about trust. Something felt.”

The exchange is mutual. The photograph records an encounter rather than a capture.

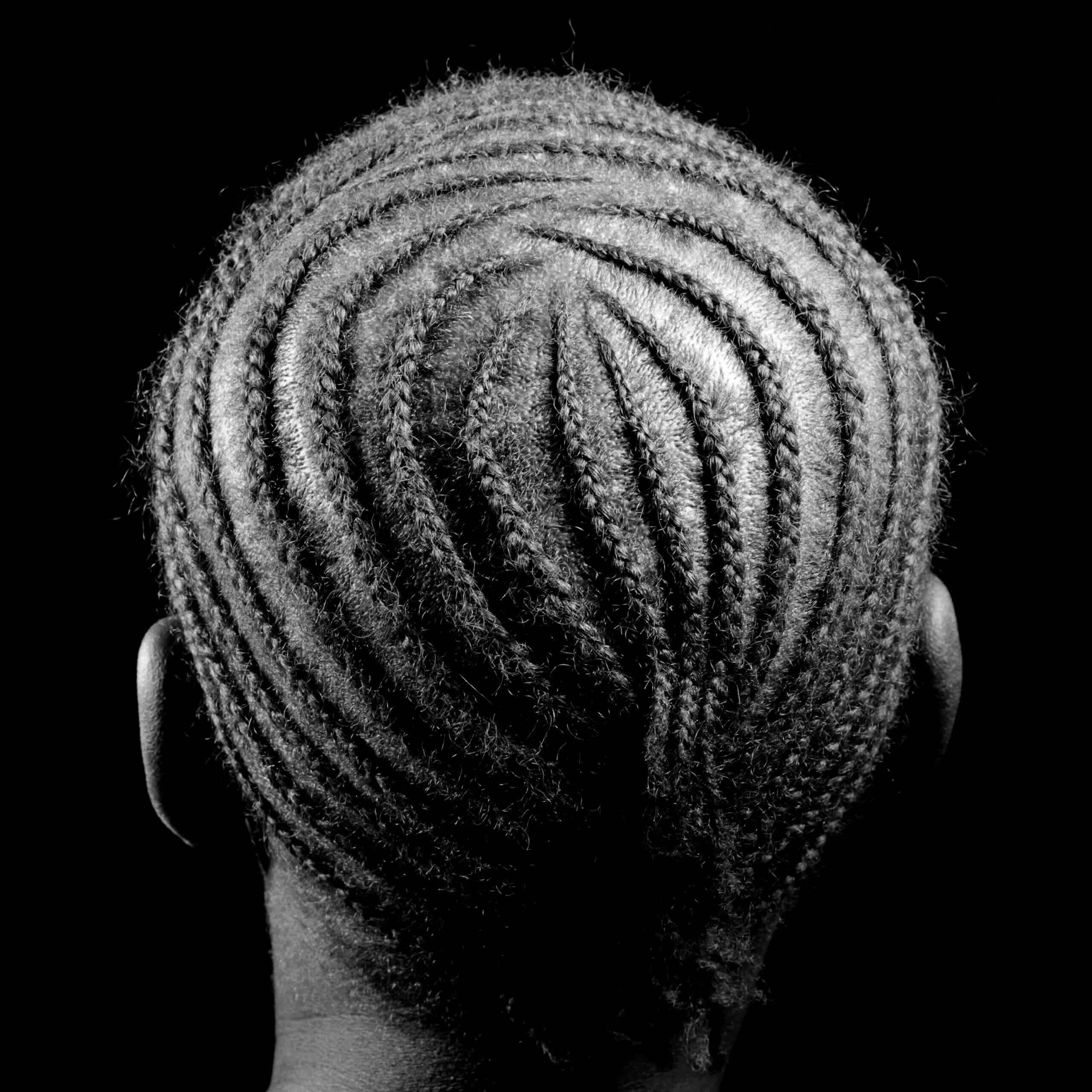

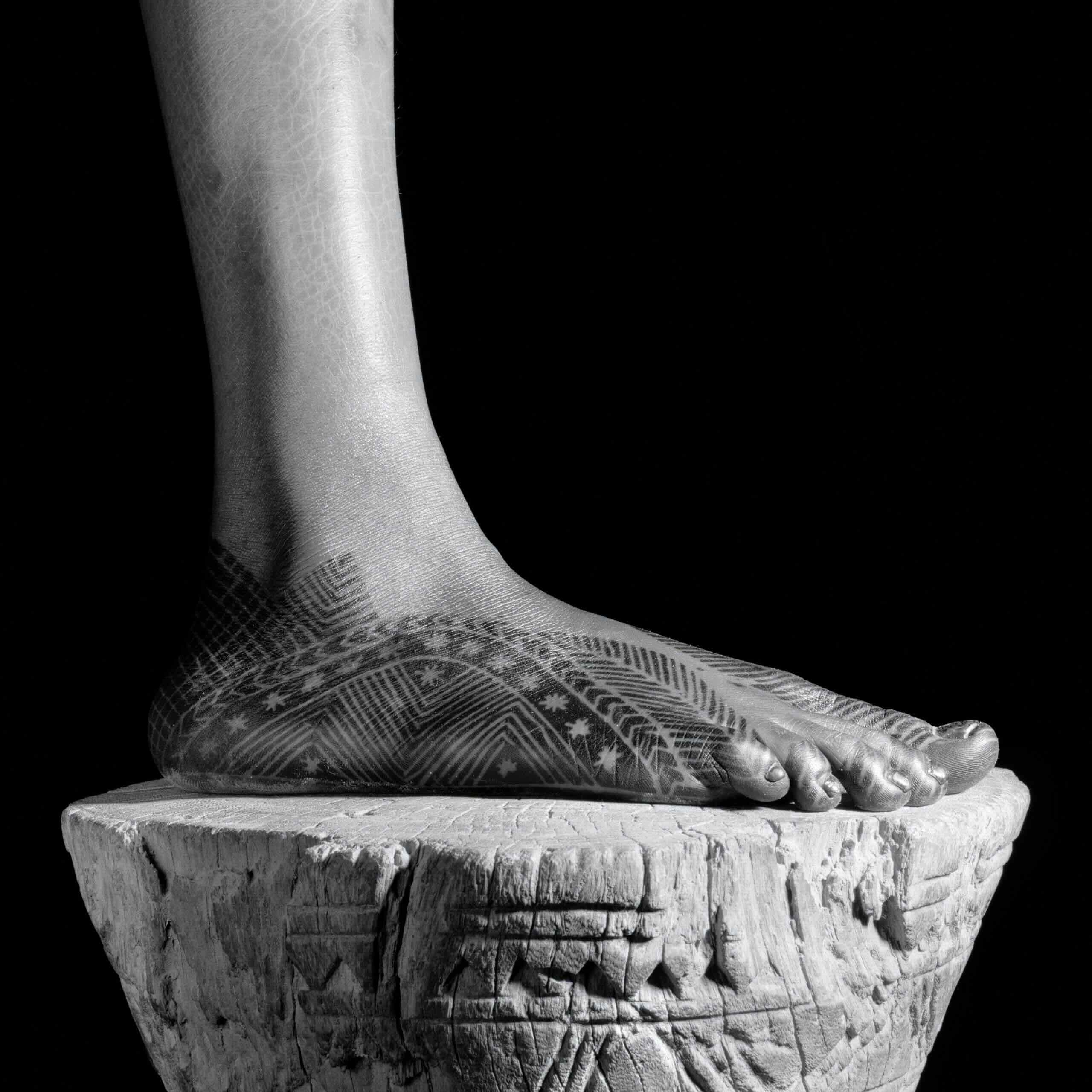

The Flower Children — Omo River Valley, Ethiopia

The final body of work discussed during the talk brought Huynh to the Omo River Valley in Ethiopia, a remote region requiring days of travel by car and caravan.

Luntz: “When we saw these images for the first time, we were overwhelmed. There is stillness, sophistication, power.”

The Flower Children decorate themselves daily with flowers, feathers, pigment, and natural materials.

Huynh: “They do this several times a day. It is easy for them. It is between them and being in harmony with nature.”

“What is fascinating is that they don’t have mirrors. They do this pure beauty for the gaze of the other.”

Acceptance was gradual.

“For two weeks, they didn’t want me. I slept on the floor far away. Then closer. Then closer.”

An accident involving gasoline left Huynh severely burned. He returned to Addis Ababa for treatment—and then returned again.

“When I came back, they adopted me.”

Rather than bringing clothing or objects that could not be evenly shared, he brought spices.

“These are egalitarian cultures. You cannot bring something that cannot be shared equally. I brought salt, pepper, tastes they don’t know.”

One evening, he projected the images onto a white sheet so the subjects could see themselves large-scale.

“It was very special,” Huynh said. “Very intense.”

Luntz: “They own the frame. They do not feel vulnerable.”

Closing: Portrait and Light

As the conversation concluded, the throughline across Jean-Baptiste Huynh’s practice became unmistakable. Whether photographing a child in Vietnam, a young boy in India, a shepherd in Ethiopia, an oxidized mirror, a candle flame, or the sky at twilight, Huynh returns to the same inquiry: how to reveal presence before performance.

His discipline is unwavering. He has used the same camera and lens since he was seventeen. He works within the square format. He isolates the subject against black. He lights with a single source. These constraints are not aesthetic flourishes; they are structural commitments. Within them, variation emerges naturally, but the underlying intention remains constant.

Light, in Huynh’s work, is never decorative. It is architectural. It clarifies form rather than dramatizing it. It reveals surface while suggesting interiority. The face, the hand, the animal, the flower, the horizon — each becomes a site of concentration, stripped of narrative context so that the viewer confronts something essential.

When asked which body of work has been most meaningful to him, Huynh answered without hesitation: “Portrait. And light.”

The pairing is telling. Portrait, as he practices it, is not about likeness or identity in a social sense. It is about presence. Light is the means through which that presence becomes visible.

Across continents and decades, Jean-Baptiste Huynh has refined a singular pursuit: to remove excess, remove performance, and allow what is fundamental to stand quietly in the frame.